For today's podcast, Dr. J has got a treat for you! Joel Salatin, American farmer, lecturer, author, and owner of Polyface Farm. He is one of the most famous farmers with his successful, unconventional techniques (agricultural methods used at Polyface are “beyond organic”).

Dr. J is talking us through the food journey and how a strong immune system starts with our food. We open with segregation vs. integration in conventional vs. unconventional farming. The benefits are obvious, and Salatin chooses not to mass produce to maintain a holistic and environmentally friendly business model. We shift into a discussion about quality and nutrient density of foods. We look at how some recent studies, documentaries, and food movements sweep over the fact that organic grass-fed meat is of a far superior quality to fast food meat. The quality of mass produced meats, fast food “meats”, and organic grass-fed meats are all different, and Dr. J and Joel acknowledge and elaborate on this. Much is covered during this podcast, but stay until the end to learn how our food-spending habits are changing with the times. While we used to spend 18% of our income on food and less on health, now it is the opposite. Dr. J sees this need to spend more on health in direct correlation with the quality and nutrient density of today's foods. Spend more money on good quality food that is high in nutrients and you'll spend less on hospital bills, etc.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani

In this episode, we cover:

00:00 Intro to holistic farming

07:01 Junk food epidemic

19:47 Food processing plants

26:16 Politics of food

31:10 Nutrient-dense food

37:00 Plant protein vs animal protein, bacteria, biomass and the climate

44:24 Food labels and grading system

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: And we are live! It’s Dr. Justin Marchegiani here in the house with Joel Salatin, who is one of the most famous farmers out there who runs Polyface Farms, an organic natural farming association. We’re gonna talk about all things farming, health, immune system. Let’s dive in. Joel, how are you doin’ today?

Joel Salatin: I’m doing great and it’s an honor to be with you, Dr. J.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Oh, thank you so much. So, I first came upon you, how long has it—maybe 10 years ago now? In the documentary, Food Inc? Has it been 10 years?

Joel Salatin: Yes, it has been 10 years.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Wow! I remember that movie. There was a couple of things. It really kinda juxtaposed conventional farming methods. You bring in the cows then you bring in all the corn and then you have to move everything out. Get the corn you know—get all the cow patties out because of all the toxins that happen in it and then you see this wonderful juxtaposition where you have these cows, you move them throughout the pasture. You bring in the chicken to eat the remains of the stool they bring. You have this beautiful synergy in your farming and it was like this complete circle where the conventional system was just so, let’s just say, it lacked that holistic nature. Can you just kinda juxtapose, you know, the farming on the conventional side this with the more holistic farming just so the average person—

Joel Salatin: Right.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: That’s stepping into this, understands the difference?

Joel Salatin: Sure! Well, you’ve laid it out very well. One of the big differences is segregation versus integration. I mean—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Right.

Joel Salatin: In the industrial system, the animals are segregated from their environment, from their feedstocks. They’re cooped up in a house. They breathe in their own fecal particulate all day.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Correct.

Joel Salatin: Their waste goes into whatever lagoons. I mean, if North Carolina didn’t get a hurricane every 2 years, the whole state would be full like a toilet tank right now.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Uh-hmm.

Joel Salatin: You know, from all the clogged lagoons. Where—and then it goes to, you know, to wherever the food gets, to wherever it goes, into a great huge processing plant that’s also segregated with razor wire and no trespassing zones from its own community. Whereas in our system, it’s a highly decentralized system, a highly integrated system where the environments of open land, forest land, and water integrate closely. Wildlife is not considered a liability. Wildlife is considered an asset.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Correct.

Joel Salatin: Pollinators are encouraged and so the animals are each in a habitat that allows it to express its phenotypical distinctiveness. We call it the pigness of the pig, the chickeness of the chicken, ah so that they can fully express their, you know, yeah, their physiological uniqueness.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Totally makes sense.

Joel Salatin: The animals are moved from paddock to paddock. The chickens come behind the cows. The cows eat grass. I mean, they are herbivores so they don’t grain and they certainly don’t eat dead chickens and chicken manure like the industry feeds them and the manure fertilizes the pasture like the bison did that built the great soils of, you know, America and then we process locally and we, you know, we feed our foodshed and so everything is this circle. I mean, even our composting, we build compost with pigs. So instead of using—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Wow.

Joel Salatin: Great big machines, you know, to turn these piles, we actually just put some corn in it, turn in the pigs and the pigs aerate it and stir it like a big egg beater and of course, the pigs love to do this. We are not asking them to do something they don’t like to do.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: 100%, I like it and I’m not an educated farmer but I could just see the holistic in this and the synergy and it just made sense. Now obviously, there’s business and, you know, the whole market type of feeds, this conventional type of way of living or producing animals in a conventional way, is it possible to still make money as a farmer and produce food holistically like this or is the profit mode of just really, really change the direction in how farming is moving?

Joel Salatin: Well, absolutely. It’s possible to make a living this way. That’s what we do. We’re not a non-profit. We are a for-profit outfit and now, that said, it’s important to realize that much of the food sold in the supermarket is not honestly—the cost of that is not honestly gathered. I mean, the fact that we have a dead zone the size of Rhode Island and the Gulf of Mexico, that is a direct external cost of industrial agriculture or the fact that half of all cases of diarrhea in the United States come from foodborne pathogens. You know, what’s the case of diarrhea worth? I don’t know what it’s worth but it’s not very fun and so we have all these additional costs that are not captured in the supermarket price and so we say, we’re the cheapest food on the planet because we are not polluting anybody. We’re not, you know, we’re not polluting anybody’s, you know, backyard barbecue with a stinky air and we’re not giving anybody a case of diarrhea and we’re not giving anybody MRSA and C. diff with subtherapeutic antibiotic use. So there’s—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: I just wanna interject real quick. You said, “A dead zone in Mexico or the Gulf of Mexico?” Can you elaborate a little more on that?

Joel Salatin: Yeah, well the Gulf of Mexico, of course, is the ocean and the right now, in the Gulf of Mexico there’s a dead zone which is a toxic—where there’s no oxygen and nothing grows and it’s the size of Rhode Island right now and all those trip fishermen—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah.

Joel Salatin: Fisherman that made a living in that large area, there’s no longer anything produced there.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Oh, wow. I didn’t know that.

Joel Salatin: Yeah. So I mean, it’s big. I mean, it’s the biggest dead zone on the planet right now.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Interesting.

Joel Salatin: And not mention the many that are just, you know, internal but no, that’s a direct result of industrial, chemical and you know, run-off down the Mississippi.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Oh, I see. So it’s caused by the pesticide run-off and it’s creating a dead zone where just life can’t happen because of all—

Joel Salatin: Right.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: The toxic soup that’s happening there essentially.

Joel Salatin: That’s right. That’s right.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Okay, very interesting.

Joel Salatin: That’s right.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: And you have really touched on it too much, I’ll dive into, I wanna get thoughts on it is there is an inequality in regards to junk food being cheap partly because of a lot of the government subsidy, right? 20 billion dollars or so for wheat and soy, so when you throw that on, it’s gonna make these foods artificially sweet so when you see the Dollar Menu for instance, it’s really not a dollar, it’s probably orders of magnitude above that. Can you talk about the junk food epidemic with high fructose, corn syrup, soy, all these refined processed foods and how they’re artificially cheap?

Joel Salatin: Well, sure. I mean, the entire whatever farm program, USDA program, is dedicated toward subsidizing, concessionizing A) not only a large-scale enterprises to the exclusion of small-scale enterprises.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Right.

Joel Salatin: And you know, amalgamation and centralization and all that, but also to certain products, certain crops. There’s only 6 crops that get subsidies. Now they call insurance because subsidies have become you know—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Right.

Joel Salatin: Too politically incorrect.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Too politically, yeah, exactly.

Joel Salatin: So now they call insurance. But there’s only 6 products that have that you know, corn, soybeans, wheat and rice.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Granola?

Joel Salatin: Uh, not granola. Cotton.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Cotton.

Joel Salatin: And the other one is sugarcane.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Wow.

Joel Salatin: Sugarcane. So those are the 6 crops that are officially in that, you know that, kind of—well, the old subsidy program now the new insurance program, and so anytime you have incentives for just 6 commodities, guess what? You’re gonna get a skewed cost structure and an inordinate amount of production in those particular commodities and so that’s exactly what’s happened. And of course, you know, when you talk about junk food, you gotta realize that junk food is not necessarily less expensive than nutritious food. I mean, a Snickers bar, the price per pound of a Snickers bar is more than the price per pound of our, you know, grass-finished beef for example.

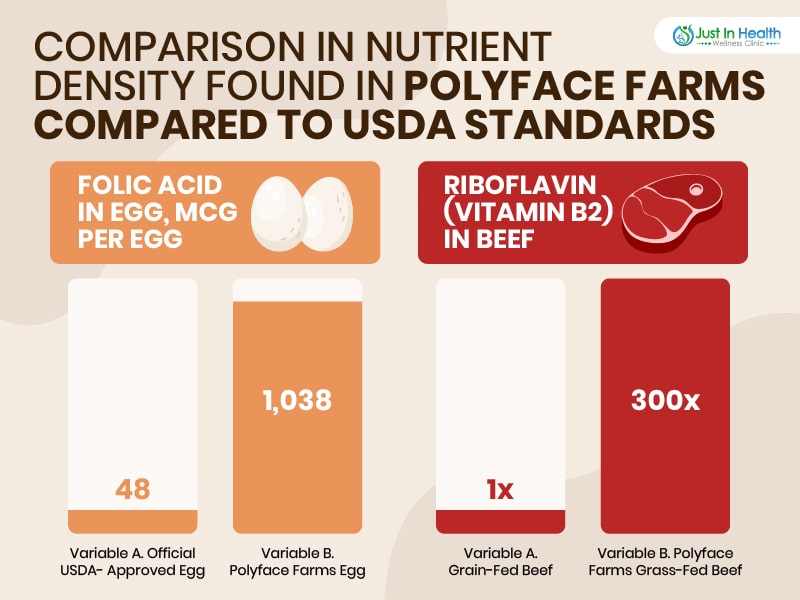

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: I think I heard you once say this, I mean, you can correct me if I’m wrong. I think you were talking about your organic eggs versus the conventional eggs and you’re like, “Hey, yeah. This is the twice the amount of cost but do you know that the amount of folate in here is 20 times more.” Can you talk about the nutrient density? And is that about correct? Is that number about correct? From the quote from before? In regards to the folate and eggs?

Joel Salatin: Yeah, so we participated with Mother Earth News Magazine.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah.

Joel Salatin: In a study back, oh I don’t know, 5 or 6 years ago. They got tired of people—of being whatever panned and excoriated for saying that there was a difference from carrot to carrot, egg to egg, you know, pork chop to pork chop and so they said, “Well, let’s do it. Let’s take, you know, pastured eggs. Let’s find some farmers and settle this dispute.” And so they got 12 of us and we send them to a lab and they measured it for 12 nutrients. One of them was folic acid and the official USDA, you know, nutrient label for eggs is like 48 mcg per egg of folic acid and our eggs averaged 1,038 mcg per egg.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Wow.

Joel Salatin: No, I mean, yeah, so your magnitude of 20—this isn’t a 5% difference, a 10%. This is like, you know, magnitudes. The same thing is true with like grass-finished beef compared to corn-finished beef. For example, riboflavin. Riboflavin is especially—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: B2.

Joel Salatin: You know, yeah, and it was like 300% higher.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Wow.

Joel Salatin: And, and so you know, these products. When you talk about a salad bar, you know, being able to exercise and fresh air, and sunshine and/or grass in a salad bar where they’re moved every day to a new spot and you get this fresh salad. The keratins in that salad completely changed the fatty acid, the nutritional profile—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Exactly.

Joel Salatin: Structure of the, you know, of the meat, poultry, egg. You know, whatever it is on the protein.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: And this primarily just has to do with the fact that the cows are eating a natural diet. They’re getting lots of greens and then of course, the greens aren’t gonna be laden with GMOs and pesticides and then you’re cycling that through, and then you’re providing the synergy in with the chickens that eat the fecal debris afterwards, which then re-fertilized, and then it just creates this healthier microbiome. Healthier microbiome in the soil. Healthy soil microbiome creates more nutrients in the grass and then the circle just continues. Does that—

Joel Salatin: Right.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Sound about right?

Joel Salatin: Right. Yeah, you’re in the ballpark. Essentially, the diversity in our microbiome can only be as diverse as the diversity that we’re feeding it in our food and that can only be as diverse as the soil food web in the soil. I mean, every like tablespoon of soil has more beings in it—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yup.

Joel Salatin: Than there are people on the face of the Earth.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Exactly.

Joel Salatin: And so if we—so if we reduce half of the soil bacteria, you know, with chemicals and make it simplistic and then we only do mono speciation of plants and animals growing on that soil, and then we send that into a sterile processing facility and what comes out as sterile, there’s not much there to feed our microbiome.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Exactly.

Joel Salatin: And so, you know, when I go pick a carrot out in the garden, I don’t even wash it off. I rub it off on my pants and get a little bit of that dirt. You know, I can always imagine these dirt like the acetobacter and mycorrhizae.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yup.

Joel Salatin: They come in and they go down and I swallow them and they hit their destined cousins down in my gut, right?

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah.

Joel Salatin: Like, “Oh, hello, cousin. Where have you been?” Yeah, you know?

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah.

Joel Salatin: And they have this family reunion of microorganisms, you know? I can just–

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: That makes so much sense.

Joel Salatin: Going on.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: That makes sense. Are there any bigger companies like Tyson or any of these bigger farming companies that are trying to do what you’re doing on a larger scale? Obviously, they’re doing it because they feel like they can be more efficient in how much product they produce. You know, we can argue about the quality aspect as you already just did with the nutritional density on the carrots, on the eggs, and I imagine that goes with the grass-fed meat.

Joel Salatin: Yup.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: And the vitamin B2. So there’s a nutritional density component that they are not measuring because I think they get paid by the pound, not by the nutrient, right?

Joel Salatin: That’s right. Nobody in the indust—nobody in the food system gets paid for nutrients right now. Now that may change. I mean, there’s some cool technology coming out with little handheld spectrophotometers.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Wow.

Joel Salatin: You know, which is Abby’s machine on NCIS, you know? The mass spec that she’s always got.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yup.

Joel Salatin: And so there’s some interesting technology especially now in produce where we’re trying to measure, you know, wavelengths. So there’s some cool stuff coming but yeah, you’re right. In the food system, nobody really gets paid for nutrition. They get paid for pounds and bushels and of course, that is not a measure of—that’s not a measure of quality. It’s a measure of quantity but it is not a measure of quality. It would be like measuring the effectiveness of a college by the number of diplomas it produced rather than the quality of jobs that graduates got.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Love it. Great analogy. So essentially, we have a system that is really good at getting animals fat and big, which then they get paid more because of the weight versus healthy and nutrient-dense—

Joel Salatin: Yes.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Which then provides more health to the consumers and I just—I tell my patients when they’re going out shopping, you really have to change your mindset when you’re shopping. You have to say, “Hey, how can I get the best price? No, “ How can I get the most nutrients for my dollar?” And when you do that, the organic higher quality, more local foods will always give you more nutrients per dollar versus more bulk per dollar.

Joel Salatin: Right. For example, in beef production, a lot of people are familiar with ionophore either implants or supplements in like a mineral box. Well, these ionophores are basically steroids. They don’t actually increase mass. They increase the cell’s ability to hold more water and so you get more weight but you don’t get more nutrition. I mean—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Ahh.

Joel Salatin: The poultry industry right now, I think Tyson sells something like a billion dollars a year worth of water because they put chickens in chill tanks and agitate them so the birds take on water and the industry—like 10% of the weight of a bird in a supermarket is water. And so there’s all sorts of little tricks and techniques to try to, you know, abscond a few more pennies for nothing out of the supermarket which is why we promote actually just circumventing the industrial food chain. Whether it’s a Farmer’s Market, an on-farm store, a farm that ships to you, you know, directly to your doorstep. I mean, there are now all sorts of alternatives to the mainline orthodox food system and all of those offers, in general, you know, better alternatives than you can find down at Costco and Walmart.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah.

Joel Salatin: Where the only way to get into those places—several years ago I had a bunch of—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Uh-hmm.

Joel Salatin: Costco vice-presidents here and we—they spent the day. They were excited about what we were doing and they asked me then at the end. They said, “So how we get your stuff in at, you know, Sam’s Club and Costco?” I said, “Well, the first thing you have to do is let a truck smaller than tractor-trailer back up to your dock.” That was the end of the discussion. They could not even—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: There wasn’t enough scale.

Joel Salatin: No, they couldn’t imagine a system where a truck smaller than a tractor-trailer back up to their dock. So, you know, this was the kind of—it’s a prejudice within the marketplace that excludes, you know, positive alternatives.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Right. Essentially, they’re looking for more scale and this is more of a decentralized way of doing it just because of, you know, it’s the big companies are kinda wetted to this conventional system because it’s all a weight-driven system not a nutrient-system so you kinda have to change how the system for it to make sense on the financial side to grow. I mean, is it possible like if you had more money right now if someone gave you a hundred million dollars, could you scale this thing to the size of a Tyson, while producing the same food quality?

Joel Salatin: Sure. So what a great question and you know, our most questions and criticism is price and scale. You know, can you actually feed the world this way and so the way I envision it is to explain to people absolutely this scale, in fact it scales just fine but it doesn’t scale like an aircraft carrier, it scales like a million speedboats.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah.

Joel Salatin: And so we believe in scale not by taking something—not by taking a stationary piece of infrastructure and turning it into a mega, you know, infrastructure but rather a whole lot of decentralized, democratized—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Right.

Joel Salatin: Infrastructure all over the landscape so that instead of 150 mega-processing facilities worth 3,000 employees, the country has maybe, you know, 50,000 smaller scale abattoirs or canning plants or processing facilities scattered all over the landscape devoted to their own food, you know, their regional foodsheds.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Right.

Joel Salatin: And so one is scaled by duplication, the other is scaled by whatever, you know—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Subsidy or?

Joel Salatin: Empire building.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: The Empire Building.

Joel Salatin: Build a bigger coliseum instead of building a whole bunch of little theatres.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Right. Now that makes sense. There’s a quote by John Paul Getty, “You’re better off getting 1% out of 100 men than 100% out of 1 man”, right?

Joel Salatin: Yeah.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: So it’s kinda like that? And it’s probably safer for our food supply. I mean, you can go read—you read stories of Russia before the revolution where all the starvation and stuff would happen and you know, because you had one farm controlled by the government and then that went sideways, and everyone starved, right?

Joel Salatin: Sure, yeah.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: So it makes sense from a safety standpoint for sure. Let’s talk about food processing plants right now. There’s a lot of hoopla where things were closed off because of the COVID-19 thing and then they had this big supply chain that was moving and they had to kill animals off because that supply chain couldn’t move and the supply chain was so tight in how they brought animals in, fed them, brought them to slaughter. If they couldn’t slaughter them on time, the whole thing got backed up and they had to kill them. So you have this supply chain backup. You have the whole food processing plant owned by a lot of companies outside of the country that are—it seems like they’re selectively choosing food from outside of the country versus inside the country. Can you talk a little bit about those politics?

Joel Salatin: Sure. So the idea there is that these processing plants, remember half, almost half of the US processing plant capacity right now is owned by China and Brazil. They’re owned by foreigners.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah.

Joel Salatin: So, you know, these companies are above whatever national politics. You know, they’re global in scope and loyalty. They have no loyalty, you know, to a culture, to a country, to a place. And so what happened was in these big plants, as the coronavirus came in, they started—they were unable to continue to operate. They had a lot of workers get sick. You gotta remember that right now, the only place in America where thousands of people are working shoulder to shoulder every day in wet, damp, cool, damp conditions is in these large-scale processing plants. It’s not happening anywhere else. And a lot of these workers are themselves living in difficult conditions. They come from Somalia. They come from, you know, all over the world and I’m not being xenophobic. This is just a fact.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Right.

Joel Salatin: Most of these workers are foreign workers. They’re trying to save pennies to bring, you know, additional family members home. So they’re crammed, you know, 10 people in a house that we would consider only big enough for 4 people. They crammed 10 and 20 people in these houses and they’re scrimping pennies so they’re eating, you know, they’re eating out of the gas station and they’re eating SPAM, you know, to eat cheaply. So the living conditions, they’re in a new culture, they’re under the stress of a new language, I mean, there’s a lot of stress in their life and stress of course, you know, reduces your cortisol, okay? And so, then you become more susceptible. My point is that these huge plants are incubators for sickness. Whether it’s COVID or anything else and so when you have a very small plant, a community plant like we co-own one that has 20 employees. It’s a small community plant and we—you know, we have 20 people and we’re spread out a lot more because, well, it’s small, you know? And there are 2 guys over on the kill ford, 2 guys in the back pack machine, 4 guys in the cut room and they have a lot of room. It’s just not shoulder-to-shoulder like these great, great, big plants that are basically assembly line. We do stuff by hand with individual knives and individual workstations and there’s a lot of room and there’s not that many people and we’re hiring neighbors and so it’s better working conditions. And so, the fact is, that the small decentralized plants are simply less vulnerable to pathogenicity of any type.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Right.

Joel Salatin: Of any type whether it’s on the food or in the people. They’re just less vulnerable to pathogenicity than the great big plants.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Oh, 100% and I remember in Food Inc that you were slaughtering a chicken outside in the open air with the UV light coming through and, you know, we’ve seen data that a lot of these coronaviruses cannot really survive more than 1 minute in 75°F temperature, 40% humidity so it seems like the sunlight or the UVC rays are really powerful natural disinfectant that you’re utilizing to help keep your food clean.

Joel Salatin: Yes, absolutely. And so a small plant, you know, has more windows. You know, workers can step outside for you know, for lunch or a break. I mean, there’s just a lot of additional, whatever, resilience in a small facility. So that was one of the big glitches in the food chain system. The other big glitch that happened was that when the restaurants were closed down, the food industry has 2 very distinct, whatever, journeys of food. It either goes into wholesale and you know, and restaurant trade or it goes into the retail trade. And as you can imagine, those 2 trajectories are completely different kinds of packaging, completely different kinds of distribution, everything. And so what happened when the restaurants closed down, everybody started buying retail, while the industry couldn’t adjust their packaging and their, whatever, their fabrication lines—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Right.

Joel Salatin: Fast enough to adjust. I mean, we even had it at our farm. At our farm, we never ran out of ground beef. We ran out of ground beef for 3 days. People were going, you know, going ballistic. We don’t have ground beef. We had 5,000 pounds of 5-lb packages of ground beef for our restaurants but that was not for the ret—you know, our retailer customers didn’t want 5-lb, you know, 5-lb packages of ground beef. They want 1-lb packages of ground beef. And so—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Right.

Joel Salatin: And so our retail customers saw us being “out” but we had plenty. It was just in bigger packages for restaurants.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Wow. That’s—

Joel Salatin: You know, so we encouraged people, we said, “Look, here’s how you can do it. You can take this all home, cook it, and then what you don’t eat, freeze it, and you can use it another time. Or you can take a hacksaw, you know, whack in quarters, you know and move.” So we were doing all sorts of creative things with our customers trying to get them to understand the meat is here, you just might have to help us and you know, meet this glitch here for a little bit.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: No, that makes a lot of sense. And just from a national security standpoint, you know, it doesn’t make sense allowing foreign people to own so much of our food supply. I mean, the gateway of our food supply being these food packaging plants. It just doesn’t make sense that they would—that such a large percent of them are owned by international companies. That is so mind-blowing!

Joel Salatin: Well, it is and you know, you can really see it right now in the last I think I’m right on this, in the last like 30 years, the US has gone from one—from roughly 1% to 5% of our food being imported to today, it’s 20%. In other words, 1 out of 5 mouthfuls of food that an American takes is now coming from a foreign place. We are becoming more and more vulnerable to these kinds of shocks within in the system. Of course, you know, during this time, China for the year leading up to the coronavirus, for that year, China depopulated half of their pork industry. You know, China consumes half of the world’s pork. Just the country of China consumes—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Wow.

Joel Salatin: Half of the world’s pork and in China, pork is the number one, you know, animal protein. In America, it’s chicken.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Right. It makes sense.

Joel Salatin: Chicken, but in China it’s pork. So when the African swine fever came into China and by the way, it decimated the large producers more than the small ones, but when it came into China they began depopulating and so China was entering this whole COVID-19 thing short of pork, and so here we were with empty store shelves and Smithfield, which is owned by the Chinese, were sending 20% of our pork to China to help meet the African swine fever shortfall in China—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Wow.

Joel Salatin: While our grocery shelves were empty.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Wow, this is unbelievable and the politics of food I think are really important because it just—you gotta have common sense with a lot of these things. And when you have a lot of these international companies running these food processing plants, they are selecting for their fellow international probably subsidiaries I imagine, so then they’re picking meat from these international companies and bringing it here and then leaving our domestic farmers in the hole, kinda empty-handed, with all these extra supply and they are just being given money for the—by the government to sit on it essentially, right?

Joel Salatin: Yeah, well, I don’t know how much the subsidies, you know, go into those big outfits. I can tell you that probably the single, you know, when you talk about the politics of food, probably the single biggest issue here is that it is not necessarily money if you will, but it’s regulatory where it’s very, very difficult for a small, you know, community abattoir to get in the business because of very scale prejudicial—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah.

Joel Salatin: Scale prejudicial requirements. That’s one reason why Congressman Tom Massie from Kentucky—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah. Kentucky, yeah.

Joel Salatin: Has put in the prime act to try to allow the intrastate, not interstate, but intrastate sale of custom processed beef and pork and so that a lot of these little community abattoirs can actually join the marketplace and aren’t excluded from the marketplace. The cost of getting into this is extremely expensive in its primary regulations. You know, you can go out and shoot a deer on a 70-degree day and feed it to your kids and give it to all the neighborhood and you’re a great American, but if you do one pig on an appropriate temperature day, you’re a criminal.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Wow.

Joel Salatin: And so this is not about food safety, it’s about market access.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Right. There’s some common sense or form that could be done, I mean, if I was the agricultural czar and I could do a couple of different things right now policy-wise to just improve the health of this country, I think number one, I would get rid of all farming subsidies. Because I think number one is you have to show people, the Americans, what the true cost of food in your junk food is, number one. Number two, I would adjust a lot of the food stamps/SNAP program. People that need food, I think you give them a stipend to actually get the real food from their local farmer so you actually get the real food and you can’t spend it on junk food and crap and sugar, and anything else because I think if people need assistance, the worse thing we can do is give them crappy food and then they end up being on more drugs and—

Joel Salatin: Right.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: And they are drained on the healthcare system because then you pay twice and you know, chronic healthcare is actually probably more like 10x, right? So I’d start with those first 2 things if I were to do anything just to let the free market, and then I probably would do more on the education side because I think people need to be educated about nutrients, not just how much their food weighs. I think it’s about value. People look at their food and they don’t have the value component. They just kinda look at it as, “Okay, it’s you know, this chicken is the same as that chicken,” and they don’t have the value component and that takes education to people like you and people like me.

Joel Salatin: Right. Well, I’m with you. I’ll vote for you. When you run, I’ll vote for you. But yes, I agree with all those things and in fact, one of the best ways to educate people is to actually put good food in their mouth. Most Americans have never actually eaten what we call nutrient-dense authentic food. I mean, this coronavirus has brought some interesting people into our farm store. A guy came in last week and you know, he had never shopped anywhere except Walmart and so he, you know, with all this coronavirus stuff, he came to us and he got a couple of, you know, 5 chickens or something and said it would take them a month. He called back the next week and he said, “I’ve never had anything like that. We ate them all in a week.” And what it was, it was his body telling him this is real nutrition, you need to eat this. Just like—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Wow.

Joel Salatin: A little anemic 6-year-old came in with his mother.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yup.

Joel Salatin: You know, this is little itty-bitty little child. Mother said, “Oh, he’s such a picky eater. He won’t eat anything.” She bought a dozen eggs. She called us the next day and she said, “He’s eating 6 eggs in a sitting.” Well, the child he was eating, but he was starving to death. He was starving nutritionally.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Wow.

Joel Salatin: And so when he got really decent nutrition, his body, you know, whatever, it woke up. You know?

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Right. Yeah.

Joel Salatin: That’s a better wokeness than the politically correct wokeness.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah. No, that makes sense. That makes a lot of sense. Yeah, when your body has the nutrients it needs, its metabolic systems run better and yeah, they literally will generate more energy which helps with the energy and focus and mood and everything. Now I’m just curious to get your take. I mean, I’d lecture my patient on whole food and how animal nutrients—animal bioaccumulate plant nutrients. So when you have the vegan-vegetarian argument versus being able to eat whole food, healthy animal products, number one, the argument tends to—it tends to create a straw man. The first argument is it tends to create all meat as conventional junk food McDonald’s meat and I think we have to be able to differentiate that. I don’t talk about the organic broccoli in someone’s backyard and compare it to the soybeans on a monoculture farm. So we have to be able to differentiate the quality of the meat, number one. And then number two, we have to look at the nutrient density like you mentioned. I know animals bioaccumulate plant matter. I think it’s something like 8 lb of grass goes into 1 lb of cow meat. So there’s bioaccumulation and when you look at the nutrient density studies comparing a carrot to liver or beef, or your egg yolks to any type of plant, you’re gonna see this increased nutrient density. Can you—what’s your argument on the plant-based nutrition side or the more the plant and animal-based side especially the animal side?

Joel Salatin: Yeah. Well, you’re exactly right. You’re exactly right. The problem is that with things like, you know, Cowspiracy and Game Changer.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yes.

Joel Salatin: They refuse to differentiate that there can be a better way to raise a chicken or a cow—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yes.

Joel Salatin: Than a poor way to raise a chicken or a cow. I’m liking it to this. It’s as if you and I, let’s say we live on Pluto. We’re looking down at the Earth and Pluto says, “Hey, that’s an interesting-looking planet down there. I wonder what their education system is. How about we get 2 volunteers to do down there and check it out?” So you and I volunteer, we jump in the flying saucer and we come down to Earth, and we happen to land in the schoolyard of the worst school district with the worst superintendent—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Right.

Joel Salatin: In a school with the worst principal and we go visit the worst classroom with the worst teacher.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yup.

Joel Salatin: Worst parents in the whole country. And we watched this for 2 days. We go back to Pluto and they say, “Well, what did you find?” We’ll say, “Man, if education is like that, we shouldn’t have any education.” You know?

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Exactly.

Joel Salatin: And that—so when you—when all of your data points are from a dysfunctional system, you’re gonna come up with a dysfunctional conclusion and that is what has driven the data points, the science, the data points of you know, Cowspiracy, the UN Long Shadow report, the EAT-Lancet report, all these, you know, anti-animal, anti-meat things are—they don’t come here to do their data collection. You know, they go to feedlots, they go to factory farms, they go to, you know, desert irrigation.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah.

Joel Salatin: And it’s all those systems rather than a truly holistic functional synergistic type system.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah, anytime someone makes an effort to create that straw man and not let—and not really argue against the premises that you’re making, that’s sophistry right there at its best. I mean, we see it all with a lot of the people talking about climate change and the methane produced by cows. Well, okay, you know, well, let’s talk about the fact that methane is significantly reduced if not totally neutral with cows that eat grass. And so, you know, we’re just supporting now an argument of cows eating more grass and keeping the grains and the corn and all that crap out of there. But the argument still—the goal post constantly gets shifted in the plant versus animal argument and I think it’s a combination of the two but we gotta acknowledge there’s a different way to raise these animals in a healthy fashion and the results totally change. And we’re not even talking about the bioavailability of plant—

Joel Salatin: Right.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Proteins versus animal protein.

Joel Salatin: Right.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: That’s a totally different argument. The assumption is that all plant proteins are absorbed and assimilated the same way and the anti-nutrients aren’t affecting any of it and also that the amino acid profile is the same. We know that animal-based amino acid profiles are gonna be more sulfur-rich and the plant-based profiles are a lot of times are gonna be incomplete and you have to combine different proteins like rice and beans, etc. Your thoughts?

Joel Salatin: Yes. So yeah, exactly so a lot of people have never heard of a bacteria in the soil called methanotrophic bacteria.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yes.

Joel Salatin: Methanotrophic bacteria lives in pasture. It doesn’t live under corn. It doesn’t live under asphalt. It doesn’t live in feedlots. It doesn’t live on factory farms. It lives under perennial grasslands. Methanotrophic bacteria in a healthy grassland, there’s enough methanotrophic bacteria. Methanotrophic is it’s a bacteria that eats methane.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Eats it. Totally eats it. Yup.

Joel Salatin: Yeah, it eats methane and metabolizes it and feeds it back to plants, okay? And so in a healthy pasture, you know, perennial grass situation, there’s enough methanotrophic bacteria in the soil to eat up all the methane from 2,000 cows per acre. That’s how constructive and regenerative nature is. Now, nobody is gonna have 2,000 cows per acre. The point is that nature has all the mechanisms necessary to make sure there’s no waste stream. That everything has a place of reconstruction and regeneration that there’s no landfill in nature. There’s no away. There’s no waste stream. Every waste stream is the beginning of something else. And so that’s—so methanotrophic bacteria—so you don’t hear in Cowspiracy, you don’t hear them talking about methanotrophic bacteria, they just talk about, you know, feed lots and factory farms and things. And so, you know, it’s important to understand that there’s a lot in the system that they’re not talking about. Even to the point that how much water it takes to make a T-bone steak. Well, they don’t measure the urine that comes out of the cow or the bacterial exudates of the biomass when healthy biomass exudes bacteria, that’s the number one coalescent for water vapor in the atmosphere. Water vapor can coalesce around ice particles. It can coalesce around little pieces of chemical or it can coalesce around bacteria. 90% of it coalesces around bacteria and bacteria just is exhaled by the biomass, trees and grass and shrubs and things. And so, when a cow stimulates through proper grazing measure, when a cow stimulates biomass production in the forage, it actually comes alive with additional exhale bacteria that allows the clouds to form, rains to come, and stimulates water. I mean, this is all out of Walter Jehne from Australia, probably the, you know, the world’s foremost, you know, climatologist, climate change guy talking about how atmospheric moisture is the Earth’s radiator and the problem is that none of these climate changers are talking about, how do replenish the radiator of the Earth? You replenish it with biomass-induced bacteria exhaling from the plants.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Uh-hmm.

Joel Salatin: And how you do that is with the proper animal pruners around the land and not continuous grazing, not overgrazing, not desertification, but proper animal management to stimulate the abundance of the biomass on the landscape.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Can you just re-say that like in 15 seconds again? It was a lot—I wanna be able to connect those bullet points because there was so much said there. Can you just kind of reiterate that just a little bit more succinctly again?

Joel Salatin: Okay, so moisture in the air, water droplets condense.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yup.

Joel Salatin: They condense around ice particles.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yup.

Joel Salatin: They condense around little pieces of chemical, cloud seeding.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yup.

Joel Salatin: And they condense around bacteria. They’re favorite one and the one that’s most conducive is the bacteria. The bacteria comes from the exudates of biomass, green material, vegetation.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Got it.

Joel Salatin: And so it’s the vegetation that stimulates the condensation that makes the clouds that helps to create functional water, you know—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yes.

Joel Salatin: Water cycle, you know, hydraulic cycles in the world.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: And is it just vegetation and the vegetation that’s coming from the cow’s actual food that they’re eating in the grass. Is that where that vegetation’s coming from?

Joel Salatin: Yes. Because if you don’t prune biomass, then it tends to become stale and dormant and doesn’t—I mean, a grass plant goes into senescence. You know, in like 60 days, a grass plant goes into senescence.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Wow.

Joel Salatin: So if something doesn’t come along and prune that grass plant, you know, it turns brown and the bioaccumulate—the, you know, the photosynthesis stops. And so it’s the herbivorous pruner, that’s why the planet has so many herbivores—zebras and elephants and you know, llamas and alpacas and caribou. The reason for all these herbivores is to keep this vegetation freshened up like pruning an orchard or pruning a vineyard to make it, you know, to make functional. So the problems associated with domestic livestock and herbivores is not the problem with herbivores, it’s the farmers and ranchers who manage them incorrectly to not allow them to do the job they were supposed to do as freshening up, you know, pruners.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: It’s excellent. It’s such a holistic cycle and everything is affected. Everything affects everything.

Joel Salatin: Yes.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: From the soils to the plants, to the cows to the atmosphere, to the gasses being produced and you know, I always tell my patients, old foods can’t cause new disease and I don’t think we can—I don’t think new farming methods will ever beat the old farming methods that have always been there because it’s just the closer you are to Mother Nature, it seems like that’s the better way to do it.

Joel Salatin: Well, that’s for sure. And nature always fills, you know, we believe here at our farm that nature’s default position is fundamentally wellness.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yup.

Joel Salatin: And whereas in the industry, they consider the fundamentally default position as sickness. So we’ve gotta make pharmaceuticals and drugs and GMOs and all these things to override nature’s propensity towards sickness. Whereas we believe nature’s fundamentally well and if it’s not well, my first question is what did I do to mess it up.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Exactly.

Joel Salatin: What did I do to override the immunological terrain? And so we’ve actually—I’ve actually co-authored a book with Dr. Sina McCullough, it just came out 2 weeks ago. It’s, the title is Beyond Labels and it’s all about going beyond, you know, beyond just the labels in food and understanding how foods produced from a, you know, a practical standpoint. How do we make food decisions, proper food decisions and get beyond just being stuck on, you know, paleo, keto, organic, whatever it is, but you know, and labels of sickness? You know? I have this. I have that. But just going all the way beyond labels in life and I would encourage folks to, you know, to see it and it’s written like a dialog from a farmer and a PhD. So it’s—and you know, it’s—so it moves, when you get tired of me, you get her. When you get tired of her, you get me.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: I love it. That makes so much sense. That’s great. And on the conventional side, you see grades like select or choice or prime, right? How does that correlate to your meat? Like where does your meat kinda plug in to that typical grading system? Obviously, that grading system does not—I don’t think look at the hormones, the antibiotics, the grass-fed or grass-finish nature of that. Can you talk about that grading system and compare it to kinda where yours plugs in?

Joel Salatin: Sure. So that grading system was started in the early 1900s when everybody was using candles, you know, tallow for candles and so the grading system was developed so that the fat content could be measured because cattle received way, way more value if they had enough tallow to make candles.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Hmm.

Joel Salatin: This was before electricity. And so the select choice in prime—that whole grading system has nothing to do with nutrition, it has nothing to do with taste, it was nothing to do with eating quality. It’s strictly a measure of fat percentage in the animal based on—well, okay, so now we got enough fat to you know, boil down to make candles to light our houses. That’s how archaic it is and yet it—this is what happens with government programs. As you know, government programs they start and even when they are, you know, a century out of date, we got electricity, they still keep them functioning. You know, one of the things with eggs for example. You know, you get a carton of eggs, it says Grade A, Grade A large eggs. I’m having trouble with my bud here. It keeps falling out. You know, when you get a carton of eggs, it says Grade A large eggs. So what does it mean? It has nothing to do with nutrition. It only has to do–

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Uh-hmm.

Joel Salatin: With appearance and the size of the air cell and the viscosity of the albumin. It doesn’t have anything to do with—but people, they see this, you know, stamp of Grade A or whatever on an egg and they think somebody has checked it for Salmonella or Campylobacter or something. But nobody has checked them for any of that. It’s strictly an aesthetic grade in the market so that we don’t get crinkly and extra-long or extra fat or whatever you know, eggs in the marketplace. And so, this is one of the big—this is one of the reasons—this is what Sina and I are bringing out in our book, Beyond Labels, is some of this background stuff, people look at these labels and they assume it means all this. I mean, like if somebody is checking all these unpronounceable things. Doesn’t the FDA check monosodium glutamate? No! It’s generally regarded as safe. GRAS.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Right.

Joel Salatin: And GMOs. Who’s checking GMOs? Nobody. They’re considered equivalent to non-GMOs, GRAS. Generally regarded I think it is—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yup.

Joel Salatin: Generally regarded as safe. You know more about that than I do. But generally regarded, GRAS. And so there are hundreds and hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of unnatural fake compounds in our food that if they get GRAS designation, nobody checks them. Any company can add them to food without any check whatsoever.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah, and there’s no real safety studies behind it or anything which is kinda sad.

Joel Salatin: No. There’s no safety studies behind it or anything. And so many of these stamps and inspections and labels, they have nothing to do with nutrition. None of these labels has anything to do with nutrition. And I think if you and I could get all the listeners here today to understand that none of the labels has anything to do or measure either A) nutrition or B) pathogenicity, you know, they don’t measure antibiotic residue. None of this stuff. That all the things—here’s the thing. The thing that consumers fear, the things that worry consumers that they would like to know, none of that is on the label.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Exactly. Exactly. The toxicity, the drug residue, the GMOs.

Joel Salatin: The nutrient density. Yeah.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Maybe even mycotoxins. Exactly. The nutrient density which is the most important thing and that kinda comes back to one other thing that, you know, I first learned about in the documentary where I first found you, Food Inc was I think it was Michael Pollan was talking about it is that the percent of our income that we spend on food today is about 8% or 9%. It used to be 15% to 18%. So we used to prioritize a lot more of our income to food quality and that prioritization has shifted and of course, the disease management and all the drugs that are being taken I think directly correlate with the lack of investment in our food quality and then we end up investing in drugs on the other side to kinda balance out the other end.

Joel Salatin: Absolutely. You know, 30 to 40 years ago, the average American spend 18% of their income—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yup.

Joel Salatin: On food and 9% on healthcare. Today, we spend 9% on food and 18% on healthcare. Those numbers have completely inverted in the last 30 to 40 years. That’s truly profound and in fact, that inversion really accelerated in 1979 when the US—I call it the US-Duh.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah, USDA. US-Duh. Yeah, that’s a good one.

Joel Salatin: Their first food pyramid, remember the food pyramid?

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yup.

Joel Salatin: And they put Cheerios and Twinkies on the bottom as you know, the most important stuff. You know, the grains and we can track our diabetes, our, you know, our obesity. We can track all these things directly to the consumption of the way the USDA had told u to eat. The fact is, the sobering fact is, if the government had never told Americans how to eat, including hydrogenated vegetable oil and demonizing butter and lard back in—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yup.

Joel Salatin: You know, if the government had never told Americans how to eat, we would actually be healthier today.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: 100% and because special interest lobby and they get their piece out of that food pyramid or that my food plate—

Joel Salatin: Exactly.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: The recommendations are based off on financial interest, not about what makes us healthy.

Joel Salatin: Absolutely.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah, and it kinda goes back. I think people need to look at it from this perspective—old foods don’t cause new disease.

Joel Salatin: Yeah.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: And if you kinda go into that kinda model, that gives you the foundation to move forward for sure.

Joel Salatin: Right and a kind of a corollary to that is that we didn’t get this pandemic because there was a lack of a vaccine.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Uh-hmm.

Joel Salatin: It’s not like a sickness fairy floated over the planet and said, “Let’s see what are they lacking down there? Oh, they’re lacking a vaccine to COVID-19. So we’re gonna sprinkle some of that down there.” You know, we didn’t get this because we lacked the vaccine or lacked something. It’s always a result of some sort of mismanagement or you know, misapplication of things and nature doesn’t like vacuum. You know? If you’re not getting enough good bugs, they’re gonna put in some bad bugs. Nature doesn’t like a vacuum. So nature’s gonna fill the void with something. So if you’re eating junk food and if you’re, you know, if you’re drinking Coca-Cola instead of, you know, good water for that matter, nature’s gonna fill that deficiency in your cell structure.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: 100% and also, I saw a study recently, because how vaccines work is, they’re stimulating the TH2 branch of the immune system that makes antibiotics. I saw a study talking about the TH1 branch of the immune system and how other coronaviruses that we’ve been exposed in the past, our TH1 immune system has kinda been primed so a lot of the high amount of asymptomatic cases, these are people that get the infection, show no symptoms, are infectious maybe for a week but then develop antibodies long term. A lot of the reason why they were asymptomatic is because they have a TH1 immune response to the virus and the TH1 is like our natural killer cells, right? This is like in the army, there should be like the Navy Seals or the Delta Team. These are the first responders to go in first. Think of the antibodies as the infantry that comes behind alter, so you take a vaccine to increase the infantry but the TH1 immune system which is typically ignored—part of good health, good nutrition is gonna help increase that TH1 immune response and that’s part of the immune system we totally forget about.

Joel Salatin: Well, absolutely. You know, that’s so fascinating they way to hear you describe that which is really cool because I was just on a podcast not long ago in person and they tested every guest for coronavirus antibodies.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yup.

Joel Salatin: And with a blood test and so you know, the doctor came and he pricked my finger and took my, you know, took my blood and it was like a 15-minute test and he said, “Well, you know, you haven’t had it.” I said, “Well, have I been exposed to it?” He said, “Well, the antibody test only tests your secondary immune system because if your first—like if your first, like if your skin, if your exterior immune system was good enough, it will never even get into your antibodies.”

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: That’s the thing.

Joel Salatin: So he said, “I can’t tell you if you’ve been exposed. All I can tell you is did it get through your first immune system, not your second immune system.” He said, “That’s all I can tell you.” And I thought, my goodness, as much as we can’t even tell that, that’s incredible what we don’t know.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: 100%! We forget about that TH1 immune responses. There have been studies with people that if they have gammaglobulinemia, meaning they don’t have the ability to make antibodies and if these people have gotten exposed to infections and have been able to fight it off because of the TH1 immune system, which we don’t really have a great way to measure because it’s not like you make a natural killer cell specific for the COVID-19 where you can go test it. Where antibodies, they’re a specific locking key that you can test for herpes or for chlamydia or for COVID, right? You can test it.

Joel Salatin: Right.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Because there’s a specific shape of it. You don’t quite have that same, you know, I’m not an immunologist but you don’t quite have that shape recognition on the TH1 immune system where you can go look for it specifically. So it’s a little bit tough—

Joel Salatin: Right.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: To measure.

Joel Salatin: Right, yeah. And you know, and that just shows how trying to reduce everything in life—to reduce everything in life to some sort of empirical hard, whatever, formula, ratio—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Right.

Joel Salatin: Material is just—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yup.

Joel Salatin: I mean, this was the problem with the Human Genome Project. You know, remember when the Human Genome Project launched?

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Uh-hmm.

Joel Salatin: And they said, “This will take, you know, this many years and we know based on mathematical statistics that based on genetic variability, we know there will be a 100,000.” I remember it like yesterday, “There will be a 100,000 pairs on the DNA strand.” Well, goodness. This has to be the only Federal Government-funded project that ever finished at half the budget in half the time. The reason isn’t because they only found like what 24,000 pairs.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah.

Joel Salatin: I said, “That’s mathematically impossible.” And that launched the entire new, new sphere of study called Epigenetics, which is how—which is the hanky-panky, the hanky-panky going on up and down the DNA strand. Nobody knew that before and so it’s amazing how we—as we western empirical, you know, Greco-Roman Western reductionist linear compartmentalized thinkers try to break apart these pieces, life becomes more magnificent, more mysterious, more awesome, more complex, more beautiful than anything we can imagine. And so why don’t we just—why don’t we just back up and enjoy the beauty? And let’s drink water instead of Coke and let’s eat, you know, real carrots instead of make-believe carrots and real cows instead of make-believe cows, and let’s just back up and enjoy that nature is way more beautiful and complex than we can ever try to break apart anyway.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Totally. I think that really just summarizes everything. Just to kinda piggyback on the whole DNA project. I remember this. I was in college at the time and I remember what, 98% to 99% of all DNA they labeled as junk DNA because they didn’t understand it, right? Junk DNA are these DNAs that are non-encoding, right? They’re not essentially encoding proteins. Turning off right? And turning on. And that’s where I think a lot of the Epigenetics plays into. They just labeled 98% to 99%–

Joel Salatin: Right.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Of all DNA they didn’t understand that wasn’t encoding things as junk, which is unbelievable. The hubris in science to just label—

Joel Salatin: Yes.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: 99% of something junk but I think that’s where a lot of the Epigenetics play in and we know nutrition and sleep and hydration and managing stress—

Joel Salatin: yes.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Really control a lot of that DNA that we don’t understand and we just label junk.

Joel Salatin: Yeah, that’s right. I mean, it’s similar to black hole in the cosmo—in the cosmic, you know, physics to labeling black hole because somehow when you don’t appreciate the electrical components to the universe that you can’t mathematically justify all this just with gravity and mass and so well, we gotta have a placeholder to make the math work so we’ll call them black holes. We have never seen one. We don’t know if they exist but the math doesn’t work and so we humans in our finiteness, you know, we’re always coming to this big thing trying—we try to make the complex too simple and we try to make the too simple to complex.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yep, I 100% agree, Joel. I think you did a wonderful job summarizing that. How can listeners support you? I mean, can they buy your food online? Do you ship it? How can they support you? How can they support other people like you? What’s that next step?

Joel Salatin: Okay, so yeah, there’s an entire, you know, network of people like us and yes, and we do ship. We do ship now. We started it last year. We ship nationwide.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Excellent.

Joel Salatin: So yes, you can call us up and now, I’ll tell you right now we’re struggling to keep up, okay? But we’re, you know, we’re growing more. We’re doing some things so we can try to meet the demand because we’re very cognizant that this whole coronavirus thing has stimulated for the first time large-scale cultural discussions around immune function. And that’s an exciting—that’s the exciting silver lining to this whole cloud is that people for the first time on the street talking about building immune systems. That’s an exciting thing. So yes, our website is PolyfaceFarms.com and you can, you know, you can order food there and you can get information, books, you can see where I’m speaking, of course, most have been canceled but now they’re coming back. I’m actually gonna be—July 9th I’m gonna be doing 5 presentations.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Wow.

Joel Salatin: For, it’s called A Day Up The Creek With A Lunatic Farmer in Orlando, FL at the national—Libertarian Party National Convention in Orlando.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Cool.

Joel Salatin: How about that?

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: That’s awesome. Very cool.

Joel Salatin: Yeah, yeah, so anyway, yeah. PolyfaceFarms.com is our website and I’ll be glad for anybody to visit that be glad to help anybody that’s trying to get some help.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: And also, you’re an author, you have many books. You have many books as well so I imagine getting some of the books—

Joel Salatin: Yes.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Would be very helpful. I think you had a book you should recommend that kinda dovetail with this topic?

Joel Salatin: Well, certainly the book by Dr. David Montgomery on—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yup.

Joel Salatin: On soil, that’s, yeah, that’s a powerful, powerful book. I mean, there are, there’s a new one just coming out. It’s just been literally just been released by Diana Rogers called Sacred Cow.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Uh-hmm.,

Joel Salatin: In fact, I—it’s so new, I just—she just sent me it. Yeah, here it is.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Love it.

Joel Salatin: Here it is. Sacred Cow and of course, our new book, Beyond Labels is just out and it’s too far away to reach. It’s over on the other counter, but yeah, these are all books that really speak to this—you know, the whole message that we just talked about today and will help, you know, dig in a little deeper.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Is there any other ways people can donate or help besides that? I know there’s like farm to legal defense funds for some of these—

Joel Salatin: Yeah.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Farmers that are really getting hit hard with some of these lawsuits. Is that a good method? Is there a site you recommend for that? Are there any other ways people can help?

Joel Salatin: Oh yes, Farm to Consumer Legal Defense Fund is my number one recommended, you know, kind of charity in this. What people don’t realize is that as soon as you stepped out of the orthodox seat today, you step into a hearsay and hearsay is not liked by many of the government regulators and I mean, for example, they don’t even like that we love customers to come to our farm. You know, they think that they’re gonna bring disease. And so that’s why, you know, all your industrial farms, they have big, you know no trespassing signs and you know, they don’t want people—and so what has happened is we’ve disconnected so much from our food that in the industrial food, when you invest in that meal, it’s like prostitution food. It’s a one-night stand. There’s no romance or no—

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Right.

Joel Salatin: There’s no understanding of that food and so we want people to come and visit the farm. See the cows, touch the chickens, you know, pick a cherry off a tree, okay? And actually have a memory. There’s actually information that indicates if you sit down for a meal and what you’re eating, if you have a memory—if you have a memory that goes beyond that meal, then it actually helps your digestive enzymes to digest it better if there’s a memory that goes with that food. And so, you know, we’re all into building those connections of wanting people to do, but Farm to Consumer Legal Defense Fund is a wonderful organization that’s providing legal help for those of us who dare to question the orthodoxy to hold us by the hand and work us through to either fight in court or to create workarounds so we that don’t have to get a license or comply.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: You know, I’m a huge fan. I donate money to that every single year. I think it’s great and I just urge people to shift the values of food and don’t look at just price. Look at the nutrient density when you go to purchase and remember that study that Joel did there, 10x, 10 to 20x on the folate and the pasture-fed organic high-quality eggs versus the conventional. So you really get a bargain even if you’re spending you know, twice the amount of 10x more. I’ll take that deal any day.

Joel Salatin: Right.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Awesome, Joel. Thank you so much. Is there anything else you wanna leave the listeners with?

Joel Salatin: No, you’ve been a delight. We’re, I think we’re two peas in a pod here and I can’t thank you enough for taking this issue and for giving me an additional platform here and just bless you, bless you for what you do. We need a thousand like you.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Thanks so much, Joel. Really appreciate it. Love to have you back anytime you have anything else important you wanna share. Thanks again.