Living with Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) can be challenging, mainly when dealing with many gut-related symptoms. The combination of antibiotics and prokinetics is occasionally presented as a simple solution for SIBO. However, addressing gut-related health issues usually requires more than just a quick fix. In this blog post, we will examine the role of prokinetics in SIBO management and their efficacy in treating the condition and other gut-related problems.

Prokinetics are drugs or herbal supplements designed to enhance gastrointestinal (G.I.) motility – the speed and efficiency at which food travels through the digestive system. Two crucial elements of G.I. motility are:

Prokinetic medications and natural prokinetics enhance downward movement, which can be helpful for conditions where gut motility is abnormal, such as chronic constipation, constipation-dominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-C), and SIBO.

SIBO occurs when gut bacteria multiply in the small intestine instead of the large intestine, which is higher up the digestive tract than where they should be. Numerous factors can cause or contribute to SIBO. One theory suggests that delayed gastric emptying and reduced small intestine motility increase SIBO risk because the gut contents linger, allowing harmful bacteria and fungi to grow.

It might seem logical to assume that prokinetics could help combat SIBO by promoting the downward movement of gut contents. However, prokinetics may not always be the best solution for SIBO and IBS symptoms.

Firstly, while poor motility is a potential cause of SIBO, it likely affects only a small subset of individuals. Consequently, treatments explicitly aimed at enhancing motility might not be effective for the majority of SIBO patients. Moreover, even for those who experience slow motility, prokinetics may not address the underlying cause, which often involves inflammation or gut dysbiosis.

Instead of relying solely on prokinetics, adopting a healthy diet and using probiotics should be the primary supports for SIBO, underlying any additional treatments. We will look at both natural and pharmaceutical prokinetic therapies that have been shown to improve motility in SIBO and IBS patients in the following sections.

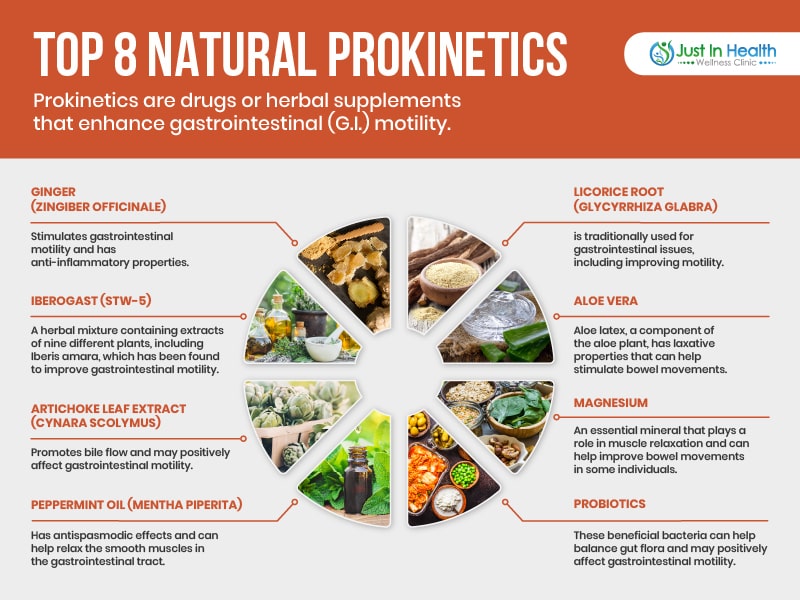

From a functional medicine doctor's perspective, natural prokinetics may be a preferable option for some patients when compared to conventional medication prokinetics. One of the main reasons is that natural prokinetics often have fewer side effects and a lower risk of causing long-term complications. Conventional prokinetics, such as metoclopramide and domperidone, can lead to side effects like dizziness, fatigue, and even the development of neurological symptoms in some cases. Additionally, some medications like erythromycin may develop antibiotic resistance when used over an extended period.

Natural prokinetics work in harmony with the body's processes, supporting overall digestive health by promoting gastrointestinal motility, soothing inflammation, and balancing gut flora. They can provide a gentler and more holistic approach to managing slow motility without causing abrupt changes in the digestive system. Furthermore, natural prokinetics like ginger, peppermint oil, and probiotics can offer additional health benefits beyond gastrointestinal motility, such as reducing inflammation, alleviating nausea, and supporting a healthy immune system. In functional medicine, the goal is to identify and address the root cause of health issues while promoting overall wellness, and natural prokinetics can play a valuable role in achieving this objective.

Natural prokinetics help promote gastrointestinal motility, improving digestion and relieving symptoms associated with gastrointestinal disorders like gastroparesis and constipation. Here is a list of some natural prokinetics that Dr. J finds to be most clinically effective:

Conventional medications for slow gastrointestinal motility target various aspects of the digestive process to help improve motility and alleviate symptoms. Here's a list of some traditional medications used to treat slow motility:

Gut motility issues, including variations in transit times, can stem from an autoimmune problem that occurs following an infection, such as food poisoning, a stomach virus, or a traveler's diarrhea. In such cases, the immune system can damage cells called interstitial cells of Cajal, which play a crucial role in regulating motility.

Testing for antibodies, such as anti-CdtB antibodies and anti-vinculin antibodies, can help determine whether this kind of immune damage has occurred. However, these tests are not always informative and may not be routinely conducted for SIBO/IBS patients.

While the autoimmunity hypothesis suggests that gut dysmotility causes SIBO, there is evidence to support the opposite: the gut bacteria imbalances and inflammation associated with SIBO may lead to gut dysmotility issues. This further emphasizes the importance of addressing inflammation and dysbiosis for individuals with SIBO and IBS.

Instead of turning to prokinetics immediately, it is advisable to tackle inflammation and gut bacteria imbalances first, allowing your gut motility apparatus and overall gut health to repair naturally. This approach has proven successful for many patients and aligns with research indicating that the interstitial cells of Cajal can repair themselves in about six months, even after significant autoimmune damage.

A comprehensive gut healing program is the most effective approach to addressing SIBO and IBS symptoms. It's essential to remember that prokinetics are not suitable for everyone and cannot replace proper nutrition and lifestyle habits.

A healthy diet is the most crucial component and the starting point for addressing gut issues. Supporting your gut microbiome with appropriate probiotics and maintaining a healthy, active lifestyle can also be beneficial.

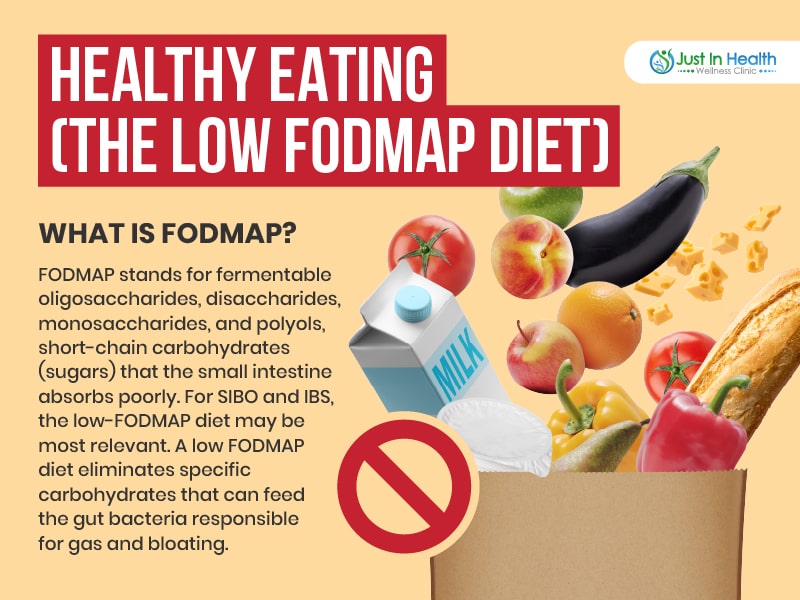

Reducing the consumption of inflammatory processed foods and sugar can immediately relieve gut symptoms. Consuming healthy whole foods, such as vegetables, safe starches that are grain-free, and healthy animal proteins, forms the basis of most anti-inflammatory diets that help control blood sugar. For SIBO and IBS, the low-FODMAP diet may be an important to tool to heal their gut.

A low FODMAP diet eliminates specific carbohydrates that can feed the gut bacteria responsible for gas and bloating. Studies have shown that low-FODMAP diets are highly effective at improving SIBO and IBS symptoms.

In addition to positive dietary changes, a daily probiotic supplement can be beneficial. Contrary to some reports, probiotics are safe and effective treatments for SIBO.

Research has demonstrated that multi-species probiotics work best for alleviating IBS symptoms. Some of the most successful outcomes for SIBO patients have been achieved when administering three types of probiotics simultaneously:

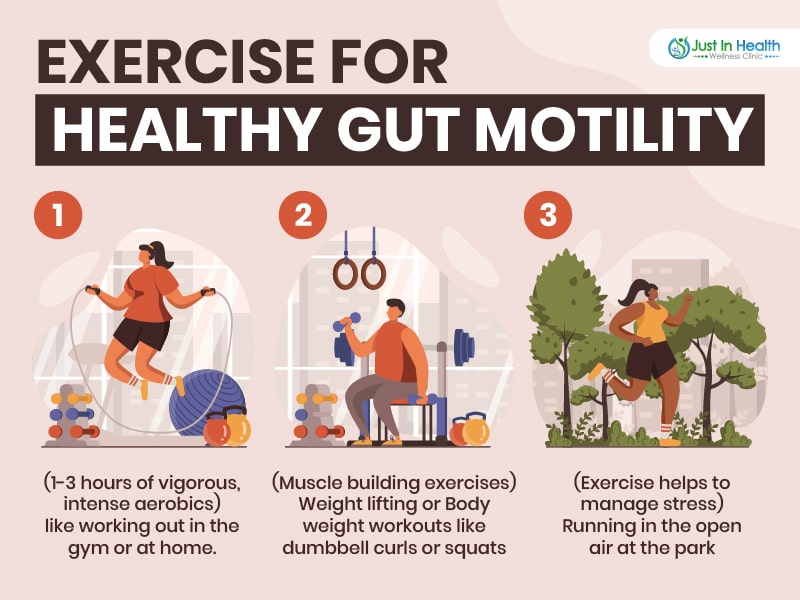

Physical activity is vital to ensuring healthy gut motility and combating constipation. Staying active and moving around promotes proper gut contractions. Each week, aim for at least 1-3 hours of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity, along with muscle-strengthening activities, on two or more days. Exercise can also help manage stress, which is known to exacerbate IBS symptoms.

Stress can negatively impact your gut health, and many people with IBS notice a correlation between stress and symptom flare-ups. To help manage stress, consider incorporating stress-reduction techniques into your daily routine. Techniques may include mindfulness meditation, yoga, deep-breathing exercises, or spending time in nature. Find what works best for you and make it a habit.

In summary, addressing SIBO and IBS symptoms involves a holistic strategy that includes dietary adjustments, probiotic assistance, exercise, and stress management. Work closely with a healthcare professional who can help you identify the most suitable treatments and strategies for your specific needs. Remember that individual responses to treatment may vary, and it may take time to see improvements in your symptoms. Be patient and consistent in your efforts to achieve optimal gut health. If you need additional clinical or supplement help, please click here to contact Dr. J.

Recommended Supplements:

References:

[1] Furness, J.B. (2012). The enteric nervous system and neurogastroenterology. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 9(5), 286-294. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.32

[2] Deloose, E., & Tack, J. (2016). Redefining the functional roles of the gastrointestinal migrating motor complex and motilin in small bacterial overgrowth and hunger signaling. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 310(4), G228-G233. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00384.2015

[3] Pimentel, M., Chow, E.J., & Lin, H.C. (2003). Eradication of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 98(12), 2700-2706. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08666.x

[4] Grover, M., Bernard, C.E., Pasricha, P.J., & Lurken, M.S. (2012). Clinical-histological associations in gastroparesis: results from the Gastroparesis Clinical Research Consortium. Neurogastroenterology & Motility, 24(6), 531-539. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01908.x

[5] Pimentel, M., Morales, W., Rezaie, A., Marsh, E., Lembo, A., Mirocha, J., … Weitsman, S. (2017). Development and validation of a biomarker for diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome in human subjects. PLoS ONE, 12(5), e0177975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177975

[6] Wouters, M.M., Vicario, M., & Santos, J. (2016). The role of mast cells in functional G.I. disorders. Gut, 65(1), 155-168. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309151

[7] Rao, S.S.C., & Camilleri, M. (2017). Review article: dietary fiber-microbiota interactions. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 46(3), 246-257. doi: 10.1111/apt.14189

[8] Schmulson, M.J., & Drossman, D.A. (2017). What is new in Rome IV? Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 23(2), 151-163. doi: 10.5056/jnm16214

[9] Mayer, E.A., Tillisch, K., & Gupta, A. (2015). Gut/brain axis and the microbiota. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 125(3), 926-938. doi: 10.1172/JCI76304

[10] Krajmalnik-Brown, R., Ilhan, Z.E., Kang, D.W., & DiBaise, J.K. (2012). Effects of gut microbes on nutrient absorption and energy regulation. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 27(2), 201-214. doi: 10.1177/0884533611436116

[11] Cryan, J.F., & Dinan, T.G. (2012). Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behavior. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(10), 701-doi: 10.1038/nrn3346

[12] Collins, S.M., & Bercik, P. (2009). The relationship between intestinal microbiota and the central nervous system in normal gastrointestinal function and disease. Gastroenterology, 136(6), 2003-2014. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.075

[13] Rhee, S.H., Pothoulakis, C., & Mayer, E.A. (2009). Principles and clinical implications of the brain-gut-enteric microbiota axis. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 6(5), 306-314. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.35

[14] Foster, J.A., & McVey Neufeld, K.A. (2013). Gut-brain axis: how the microbiome influences anxiety and depression. Trends in Neurosciences, 36(5), 305-312. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.01.005

[15] Dinan, T.G., & Cryan, J.F. (2013). Melancholic microbes: a link between gut microbiota and depression? Neurogastroenterology & Motility, 25(9), 713-719. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12198

[16] Sharon, G., Sampson, T.R., Geschwind, D.H., & Mazmanian, S.K. (2016). The central nervous system and the gut microbiome. Cell, 167(4), 915-932. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.027

[17] Bercik, P., Denou, E., Collins, J., Jackson, W., Lu, J., Jury, J., … Verdu, E.F. (2011). The intestinal microbiota affects central levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factors and behavior in mice. Gastroenterology, 141(2), 599-609. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.052

[18] Yano, J.M., Yu, K., Donaldson, G.P., Shastri, G.G., Ann, P., Ma, L., … Hsiao, E.Y. (2015). Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis. Cell, 161(2), 264-276. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.047

[19] Mayer, E.A., Savidge, T., & Shulman, R.J. (2014). Brain-gut microbiome interactions and functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology, 146(6), 1500-1512. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.037

[20] Sudo, N. (2019). Biogenic amines: signals between commensal microbiota and gut physiology. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 10, 504. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00504