In this podcast, Dr. Justin Marchegiani interviews Kat Simmons, a dietitian with a background in functional medicine who works for GI MAP Diagnostic Solution Lab. They discuss the importance of stool testing for assessing gut health, microbiota imbalances, and root causes of various health issues. Kat explains her journey from traditional dietetics to functional medicine and her passion for gut health, particularly in relation to celiac and gluten-related disorders.

The podcast delves into the GI MAP test, a comprehensive stool analysis that uses quantitative PCR to measure various organisms and their genetic material in the gut. They discuss the prevalence of foodborne illnesses and the importance of addressing these issues for optimal gut health. Additionally, they touch on the role of H. pylori, a common stomach bacteria, in causing various gastrointestinal issues and the challenges in treating it effectively.

Overall, this podcast highlights the significance of understanding and addressing gut health as a cornerstone of overall well-being, using advanced testing to guide treatment and promote positive patient outcomes.

Headsup Health free signup: http://www.justinhealth.com/headsup

In this episode, we cover:

00:33 – Introduction

05:07 – Lab Results Interpretation

09:20 – H. Pylori

15:24 – Acidity and Herbals

20:23 – Commensal Bacteria

30:48 – Opportunistic Bacteria, Fungi & Yeast

39:05 – Parasites

47:32 – Intestinal Markers

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Hey guys, Dr. Justin Martini here. Welcome back to Beyond Wellness Radio. Really excited to have Kat Simmons here today, who works for GI Map Diagnostic Solution Lab. We're going to talk about stool testing, microbiota imbalance, and everything gut-related. Our goal is to get to the root cause so that you walk away with some great actionable information. Kat, welcome to the podcast. How are you doing?

Cat Simmons: I'm good. Happy Friday! Thank you for having me. Happy Cinco de Mayo!

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Oh yeah, I forgot. Absolutely, Cinco de Mayo. Very cool. Well, nice to meet you here over the video. This is great. So, tell me a little bit more about you and your background. I know we chatted earlier. You're a dietitian by training with a lot of functional medicine training. How did you get into this field, coming from conventional dietitian land, which is, you know, a lot of times the food pyramid, lots of servings of grains, kind of an inflammatory type of diet? How did you take that U-turn, so to speak, and get into the functional medicine world?

Cat Simmons: Yeah, I mean, I went the traditional dietetics educational path mainly because I was interested in how nutrition fuels our body and makes us function. I started in the sport performance nutrition world and kind of thought that's what I wanted to do. Nutrition biochemistry is not going anywhere; it's foundational. I also have a physiology background. But then, you know, you get out in the real world and you learn what it really is. I fell… I got lucky. I got lucky, I fell into the lab scene early in my career. I took a job with a cardiometabolic laboratory where we hired dietitians to counsel and educate on lab parameters. And I fell in love with advanced testing and using labs to motivate behavior change. In fact, I don't know how you do it without labs. There's something to be said for seeing green, red, yellow on paper and motivating people to change. So, I spent a long time in cardio-metabolic, and I still believe it's profoundly important. I love where the direction of gut health is going, with some of the science that's coming out around GLP-1 and regulating the gut. I think that's kind of the next chapter. But yeah, the cardiometabolic world is super important. Diabetes isn't going anywhere, insulin resistance isn't going anywhere, obesity management's not going anywhere. But I wanted to niche down into the gut. I have a lot of interest in Celiac and gluten-related disorders. That affects my life personally. So, I took a turn, went more into the functional lab testing space in gut diagnostics, autoimmune testing, and so yeah, I've been in the lab world most of my career. I'm happy to have landed here, and I've been with DSL (GI Map Diagnostic Solution Lab) now for a couple of years, and it's a great space mainly because the GI Map is such a good tool, and it's a joy to work with in terms of driving outcomes, looking at the gut, figuring out, you know, I mean, that whole “it all begins in the gut,” you know, I believe that to my core. So, it's just fun to work and live it day in and day out. And definitely migrated more into a practitioner education space because that's needed. I mean, we're not learning this in school. I don't think any health profession is really learning this in school unless you're doing the programs that are offered by, you know, IFM (Institute for Functional Medicine) and other governing bodies. So, there's a massive need for building this education within.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah, that totally makes sense. I mean, the gut is so important. That's where 80% of your immune system is. Obviously, if you're trying to get people to make a healthy diet change but you don't have good absorption or digestion or assimilation of a lot of the nutrients you're consuming, that's a big factor. And so, I've been using stool testing with my patients for well over 10 years. And obviously, when patients have chronic stress or chronic illness, usually there's some kind of bottleneck on the digestive absorption side, whether it's hydrochloric acid enzymes, or bile that may impact the microbiome being off a little bit, maybe infections, maybe gluten sensitivity, maybe just inflammation markers. Let's just kind of dive in here. So, first off, we go to page one of the GI Map, right? We talk about a lot of bacterial foodborne kind of illnesses. How often do these come up? How often do you see them from a lab standpoint? Do they play a role with patient outcomes or patients not feeling great, like Campylobacter, the food poisoning kind of things?

Cat Simmons: Yeah, so, I mean, page one of the GI Map is sort of your rule-in, rule-out, right? It's similar to a panel that would get run in an acute setting with someone presenting with acute gastroenteritis. So, how often do you see things positive? I don't know if I had to put a number on it, 80-85% of the time you run a GI Map, this test will be non-remarkable. Everything will be less than the DL (detection limit). But we do see… I mean, there are often typical scenarios where we are seeing expression of C. diff (Clostridium difficile). C. diff is a big one. And then it's really interesting because we see very definitive patterns that unfold with the commensal microbiota. And one thing that's really tried with these really strong patterns that we walk away with in certain cases. So, C. diff, people are not always symptomatic. A lot of asymptomatic C. diff because we're not… This, what you're doing right here, this is looking at C. diff genetic genomic material in the gut. We're expressing the toxins solid with symptom assessment and maybe further testing. But C. diff does come up quite a bit.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Does it matter that it's so high? Let's say this patient here, right? They're like 100x above the reference. Does that matter?

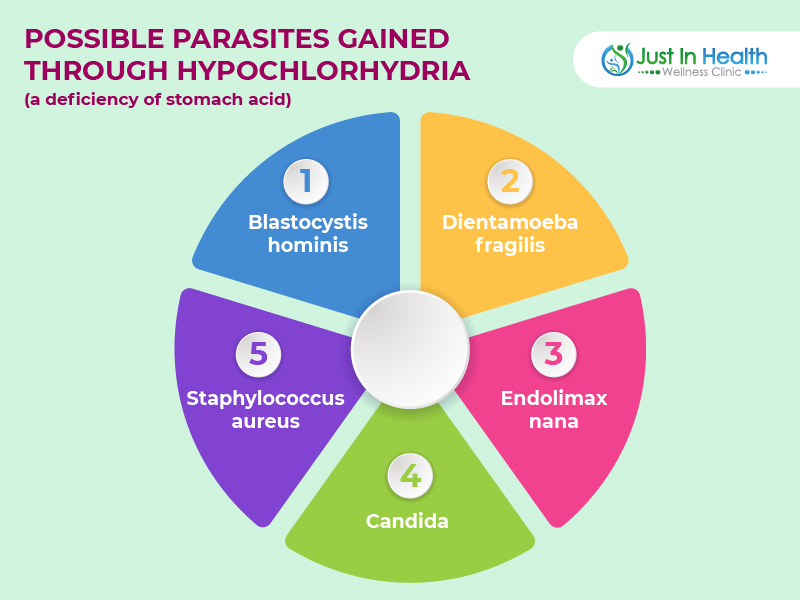

Cat Simmons: It does matter that it's so high. Yeah, it absolutely matters. And that's really a critical piece to the GI Map. The GI Map uses quantitative PCR, so we create values relative to the rest of the ecosystem. It's high. I say this all the time, with the number, we use exponential reporting. Left of the “E,” so we've got two orders of magnitude above the reference range. It absolutely does matter. But again, you'd want to do some sort of symptom assessment to see if the person… And you also look at this so you got to look at the test as a whole, certainly. Looking at C. diff carrier status, that is something that we see, you know, time to time. I deal with it quite a bit. The other page we look at a lot is low-level Giardia, which is interesting. I've seen that quite frequently. It's pretty ubiquitous in our society. It may or may not always present with acute symptoms, but you know, I wouldn't really want to see Giardia rolling around in my gut. So, most practitioners feel the same way. Whether or not we treat every time we find these organisms is a bit of an art, as much as it is a science. But you don't know what you're looking for unless you find it, and that's what the GI Map is really good at. We tend to see seasonal variations with things like Giardia because it is found in water a lot of times. So, we see low levels of E. coli, but this page is telling us about exposure, right? Usually, when we see something pop on page one, generally there are deficits in immune function. We see it with low secretory IgA. Usually, there are deficits with hydrochloric acid, so we see that reflected with digestive insufficiency and other patterns on the rest of the test that can highlight hypochlorhydria because those are our defenses, and if your defenses are down and you're exposed to these microorganisms, then your gut is more susceptible. It's just very profound patterns that we see time and time again.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: That's very cool. And clinically, when we look at a lot of these things, obviously Giardia, that's a parasite that can have a big impact. Some of these foodborne kind of illnesses, they could be transient, but they could still be a stressor in the gut, like C. diff. Now, if we go to page two and we look at H. pylori, right, we have some of these virulence factors. Can these be actually cleared out when you knock down the H. pylori, or are they kind of genetically there forever?

Cat Simmons: They're genetically there forever, but when you functionally work to lower the organism, genetic expression can change. And of course, if you're lowering the organism, the genetic load is going to lower as well. So yeah, you can see both the virulence factors, and then we also measure antibiotic-resistant genes on page five for H. pylori, and those can change based on retest if you choose to do that. But what you've pulled up here is our sample report, and it would be pretty rare to see an H. pylori profile with this amount of virulence. But certainly, the virulence factors can be really helpful at triage and decision-making, especially at those low levels. A lot of times we see say a virulence factor can trump you know whatever the number may be, typically depending on the variance factor because some of them are sort of scarier than others. A lot of times practitioners will treat regardless of the level if there are positive virulence factors.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: No, I've seen a couple of patients recently where we've treated for H. pylori using a lot of the good, kind of well-known botanicals, whether it's garlic or mastic or clove or oil of oregano, and we've had a hard time moving the needle on some of that H. pylori. Why is that? Are you seeing a lot of resistance to H. pylori, even with the botanicals? Any thoughts on that?

Cat Simmons: No, I mean, I think with mastic… Mastic is pretty well established in the literature and pretty effective. I do think dose is important, and a lot of the… You know, there's a lot of formulas out there, H. pylori formulas in the professional supplement space. In my opinion, if you look at the literature of using mastica against H. pylori, you're typically looking at like two to three grams per day. And a lot of those combo supplements don't get that high. So, I think a lot of… There's a lot of myths there that we're just not coming in with.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: I can tell you clinically, I've seen some patients where we're using that level and more, and we're still having a little bit of issues. And then, why does that happen? Is that just a resistance to the bug? Do you typically recommend rotating in different herbals until we find that right one? What's your take on that?

Cat Simmons: Yeah, I mean, it's great if you're assessing and reevaluating the testing. We don't always get that. A lot of people will treat based on symptoms, and you know, there can be symptom residual. I mean, you can have symptom improvement without lowering the number. I find mastica to be pretty effective. A lot of times, I'll combine it with some agents like DGL, licorice, black cumin seed – those are kind of the big ones. And then there's always the issue of biofilms. There's always the issue of what else is going on in the environment. There's also this whole question about stomach acid and whether or not, you know, so kind of the mechanism here for anyone who doesn't know, is one of the misunderstood things about H. pylori or just not understood is that H. pylori, I mean, obviously it's associated with the gastritis, it's an upper GI organism if it has a lot of virulence, it can be associated with, you know, the scary things we think about the ulcer diseases, the gastric cancers, acute gastritis, reflux, GERD. But beyond that, the organism itself produces this enzyme called urease, and urease can neutralize stomach acids. Yep, yep. So, a lot of times we're seeing, you know, H. pylori upstream of digestive insufficiencies. So, I do think that there's a lot of confusion out there, and you know, nothing that we do here is black and white, you know, there's just not a, we get questions every day like at what level do you treat H. pylori and what exactly do you do and do you use acid, do you not use acids. I mean, so much of this is just not black and white. But you know, one of the things I think people don't understand is a lot of times people with H. pylori need stomach acid. You look at their digestive health markers, you look at the rest of their overgrowth, like they need acid. But, and so a lot of people will bring in digestive support with acid right out the gate that may or may not be effective. Using acid while you're trying to treat H. pylori can be controversial, and it can sometimes be harder to treat H. pylori using acid because the organism essentially runs away from acid.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: It's going to go in deeper into the gut lining, right?

Cat Simmons: Right. It can, so you can kind of force it to go burrow and hide. So, a lot of times, we'll wait until, you know, 30 days into an H. pylori protocol before adding that in, and that might be a little more effective, you know, if you're, if you're having, if you're running into that problem.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: It's a different philosophical mindset of what you're doing, right, because I look at it like this: I very rarely come out of the gate killing. So, my goal is to kind of re-establish optimal physiology, optimal gut function – that's digestion, that's enzymes, that's acid. And so many of the patients' symptoms that I see get better when you improve function. It's like you improve the upstream function, the symptoms downstream neutralize. So, you want to improve function. That's a goal. If we know H. pylori is decreasing hydrochloric acid, it's probably also impacting enzymes because we need acids to activate enzymes and probably also impacting bile salt. And so then, like, let's say you're a month or two down the road, you're going to start killing. Is it worth coming in there and pausing the acid, or even adding in a neutralizer like maybe baking soda or even using Prilosec for a couple of weeks just to make the herbals more effective?

Cat Simmons: I would never really pull in Prilosec,

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: But if you're trying to not overly acidify, would it just be not adding an acid, would that be enough, or would you want to do something that actually alkalizes?

Cat Simmons: No, I don't personally pull in alkalizing agents very frequently, just because I think people have such profound issues with stomach acid. But just not using not using supplemental acid while you're trying to treat the H. pylori is pretty much where I land. But yeah, you're absolutely right, I mean, it's not always H. pylori that we need to come out the gate with. I'm with you, I don't, you know, I tend to be more conservative in killing anything, but it can always be something to deal with later. It largely depends on the person, their symptoms, what they're experiencing. If there's a really strong upper GI symptom load, then you're going to want to prioritize H. pylori pretty high.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Absolutely. And then you like to add in a lot of nutrients on the kind of soothing side, whether it's DGL or glutamine or okra or aloe?

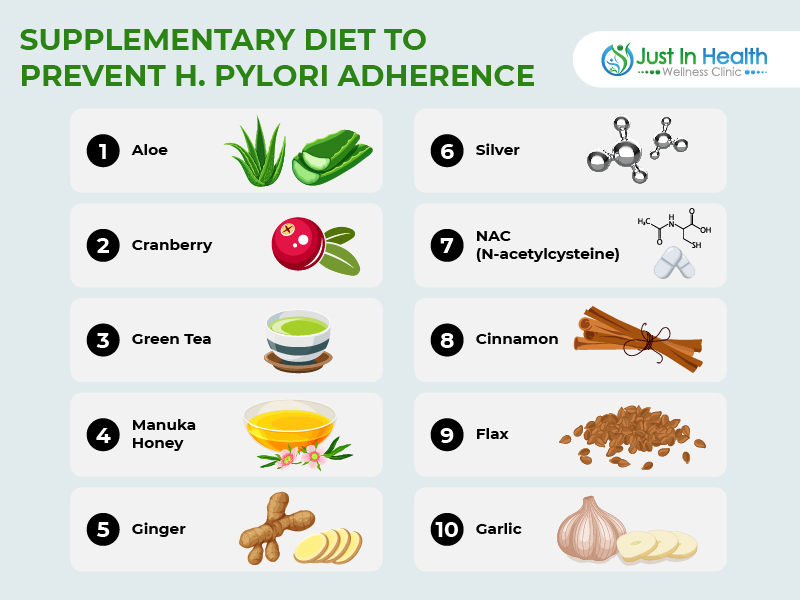

Cat Simmons: Yeah, that's great. Yep, aloe's great. And then there's a lot of things you can do with diet to kind of prevent adherence of H. pylori. A lot of these virulence factors actually work by promoting adherence, so there's quite a bit you can do to dis-promote – it's not really a word – but like to prevent adherence. Yeah, so things like cranberry can be really helpful. Green tea, you can eat manuka honey can be really helpful. And then you want to avoid things like super high nickel.

Ginger could be helpful from a motility standpoint, but high nickel is one of them, like, you know, people eat a lot of almonds, and that can be a really high nickel load. So, there's a lot you can do from a dietary perspective, even just to balance H. pylori, and it's not always about killing the organism to eradication. I mean, maybe in this scenario, like looking at what's on the screen here, yeah, that's the bug you probably want gone. But sometimes, if we're dealing with low levels and just some mild hypochlorhydria, it's really about keeping the organism in check.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: And I'll use some biofilm busters as well. Ginger's one of my favorite, I mean, Silver's up there, NAC is great, serrapeptidase. What are some of the ones that you like?

Cat Simmons: N-acetylcysteine is a good one. Cinnamon can be really helpful, particularly there's an organism on page three called pseudomonas, which is a strong biofilm former, and I'll usually pull in cinnamon when we have that on board as well. So those are probably my top favorites.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Well, foods, I know you mentioned like cranberry, avoiding the nickel. I've seen things like broccoli sprouts and blueberries being pretty helpful as well. I mean, obviously, you have things like you mentioned manuka, garlic, I've read green tea's really good, some of the probiotic-rich, like, sauerkrauts, as long as you're not getting bloated. Any other thoughts on those?

Cat Simmons: Yep, flax can be very helpful as well. Green tea, cranberry, flax, those are and honey, those are my big ones.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Great. How often do you see partners spreading things back and forth? How important is addressing the partner or the spouse so things aren't being spread back and forth via saliva and such?

Cat Simmons: I think it's an important consideration, I really do, especially if you're backing yourself into a corner, you know, the scenarios if you're not being successful with your treatment. I mean, it is a heavily transmissible organism through saliva. I mean, I have a four-year-old, and we eat together all the time. So, it just, it happens. I don't subscribe to treating to not testing and treating asymptomatic individuals just because you're treating their spouse. I would want to get that test. But I mean, I work for a lab, I like data, so that's sort of my philosophy. But yeah, I do think it's an important consideration in evaluation, especially if you're going to exhaustive efforts to help out a person. You want to look at how they're spending their days and who they're spending their days with.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah, that makes sense, I think it's important. Do you see pets as a potential vector as well for H. pylori?

Cat Simmons: Not so much, I mean, unless your dog is particularly licky and slobbery and in your face a lot. That's not something I've even really given a whole lot of thought to be honest. But I don't know, it's not something I typically… I know with cats, Giardia is pretty common, that's common in dogs too, they can be a vector in that regard for parasites, particularly not so much so with H. pylori.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Interesting. Well, let's talk a little bit about the commensal bacteria section. I get this coming up a lot with patients. I'll see patients that have a lot of dysbiotic bacteria, these things will be, the commensal stuff will be out of balance as well. I always kind of prioritize the dysbiotic stuff first because if you clean out the bad stuff, then when it comes to the repopulation phase, a lot of times with good fibers and good digestion and good probiotics, that may take care of itself. How do you kind of break this section down when you explain this to patients or people calling you up? How do you break it down? Because I mean, kind of my take out of the gate is, we have our beneficial bacteria, our lactobacillus and bifido, and then we have our big family of bacteria which is important for fiber and plant-based products to have good levels. If we're too low on that. And then, of course, we have the acromancia, which is really important for mucus production. And when I see a lot of imbalances on the higher side and I have a lot of dysbiosis, I always tell patients, wait, we're going to clear that out when we get to the big bugs, and then we'll work on repopulating with pre and probiotics on the backside. How do you address that? What's your philosophy around that?

Cat Simmons: Yeah, so it depends on the pattern, and this, I will say, that this section of the GI map is sometimes the hardest to interpret. Sometimes it's obvious, sometimes, you know, and we added these color bars and these tick marks about (which is very helpful, by the way) Yeah, I agree. I totally agree. I was part of that design plan team because, yeah, it was pretty hard to read. We had practitioners completely missing low levels like fatality bacterium, pregnancy, you know, like the reference range is 1e3. We would have people come in with, you know, 2.5 E3, and the tests didn't do anything to indicate that that was low, but it is low, very low. And I mean, look at normal. So these color bars and tick marks are vastly helpful.

And I will say, sometimes, totally see there's an obvious skew to the left or the right, you know, a lot of times sometimes we will see obvious insufficiency dysbiosis where everything's trending low, and sometimes we see obvious overgrowth when everything's trending high. And yeah, those are a little bit easier, a little bit more obvious if things are low, obviously depending on the rest of the report, but that's more of an insufficiency picture, that's more of a, we really need to come in here and rebuild and support and repopulate with all the good things that we know how to do before we do anything else, you know, really. I mean, your gut's depleted, we need to build that up. If trending on the high side, I mean, that usually indicates, it usually is downstream of digestive insufficiency where we have a lot of overgrowth, we have a scenario where there's just tons of microbes and tons of fermentation happening in the lower gut, and the symptoms of bloating and distension, I mean, how many of your patients have those symptoms, and we see that over and over again.

In terms of how do I go through this, so I always, I always take a look at the phyla first, so down at the bottom of that page, bacteriophage, we're looking at

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: How would you describe phyla? Is phyla like the big overarching family, and these things are kind of sub-family members within that?

Cat Simmons: Yeah, so go back to, you know, high school biology, kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, species. So phylum is one below kingdom. We're talking about kingdom bacteria here, so phyla is a very, very broad net. Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes together make up about 90% of healthy human microbiota populations in our gut, right? So, if in the case of insufficiency, if everything's low, if both of your phyla are, you know, at the E10 level, then you know you're just, you just don't have enough down there. Versus if both of your phyla are like in the E13, well, shoot, there's tons of stuff going on there, and that's a scenario where I would not even, don't even ask me about a probiotic right now. We don't need it. We don't need to add fuel to the fire. We (definitely SIBO for sure,) work on your digestion. Oh, well, SIBO or lower bowel, I mean, it's not just SIBO, it's, you know, Bacteroidetes are more colonic, so it's early small bowel, but we can, again, yeah, three specifically.

So this page can be tricky, and so we start with the phyla, and then we look above the bold line, and of course, you know, this is a sliver. We are looking at very well-established keystone populations here. We're not looking at every, this is not a sequencing test, we're not taking a broad stroke at everything that's in your gut, but you can get a lot of insight from, you know Escherichia, I feel like when it comes to the mucous layer, Akkermansia gets all the cred, and it is very important, don't get me wrong, but Escherichia and Akkermansia and kind of work together. So if you have both of those organisms trending low, your mucus is just not in good shape, and you can determine that, and then you can design your protocols around that. Akkermansia, like I was saying with my metabolic background, is really, research has come interplay, and its regulation of GLP, I mean, that's really exciting.

And we have more tools in our toolkit now for bringing that organism up, and then Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Roseburia butyrate producers, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is one that I look at. I look at that organism very keenly, and almost always in these inflammatory situations, things like, you know, C. difficile, it's a C. difficile carriers, i.e., you see, we see Faecalibacterium less than detectable all the time, and that relates to butyrate production through the gut, quelling inflammation, establishing immune function, establishing that gut barrier. So those are some of my favorite talk about and hone in on low, right?

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: So when you see some of these things on the higher side, bloating, gas, those kind of, those would be the big symptoms. It'll be a big sign that low stomach acid, low enzymes are present as well because you're not breaking some of these things down. What does that mean to you, big picture, when they're high?

Cat Simmons: Yeah, so we want to look at those digestive markers on page four. So, it's really nice to have those handy, refer to those. Sometimes I look at those first, sometimes refer to them throughout having that die-off, you know, hypochloridia, and digestive insufficiency are huge risk factors for overgrowth and mal-digested protein. When we get to page three and talk about these three opportunities, a lot of the more inflammatory organisms differentially ferment protein. And if you've got protein in the diet, got mal-digestion, overgrowth of organisms that produce protein, well now you're looking at things like P-Cresol, isobutyric acid, and those are just, it becomes this vicious cycle of weak digest overgrowth, inflammation, toxicity, cellular toxicity as well.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Absolutely. Now, when you see low Akkermansia, do you like to add in Akkermansia typically, kind of as in the prebiotic phase, maybe after you do gut killing?

Cat Simmons: Yeah, it kind of depends on what's going on. So, are you referring to that new Akkermansia product that's available?

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yes, yep, yep, that's correct. The one that's been out for a year, but I think it's by Pendulum.

Cat Simmons: Yeah, so I, I like that company. I think there's some really good research coming out of them. You know, I don't know, it's, you know, a lot of times we're really prioritizing for patients. So, you know, having an extra one organism supplement, it's not always in my protocol, let me tell you, let me say that. But I am certainly considering, I'm certainly considering it when there's metabolic dysfunction. But you can also do a lot with Akkermansia with red polyphenols in the diet, polyphenol-based supplements, red powders that you can add to foods or smoothies, things like that. Intermittent fasting is also a really good way that organism grows up in the fasted state. So, I'm not big on extremes in fasting, but just, um, lengthening out the overnight fast, which can also help, you know, um, Akkermansia helps regulate serotonin and through the gut, so a lot of our vagal nerves stimulate increasing Akkermansia. It's all for that same goal of enhancing motility as well.

So, yeah, I mean, but we have seen that Pendulum product effectively raise Akkermansia on GI map. I mean, as you would, as you would hope it would. It's just a matter of how, how lasting that is, you know, now are we like, do we need to take this forever? Will that come down if we stop supplementing? Like those are the things we don't really know yet.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: And the goal really is to build up that mucous layer, right, to help with the gut permeability, to help with digestion because when we have that really inflammation, a lot of gut inflammation there, that gut's going to be a little bit more raw. So building up that mucous layer is kind of the goal with that Akkermansia, correct?

Cat Simmons: Right. Yeah, yeah,

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Cool. All right, so that's helpful. Anything else you want to add here, kind of clinically, of what we'd want to think about or focus on here?

Cat Simmons: Yeah, I kind of lost you for a second. Anything I want to add related to this?

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah, anything else you wanted to add clinically, kind of related to this section of the test here before we go on to the dysbiosis section?

Cat Simmons: You know, other than digestion, is looking at this section next to secretory IGA. You tend to see all the sufficiency, low levels of those pretty inclined, secretory IGA. They go hand in hand. That's a good clinical Pearl that a lot of practitioners don't always connect the dots.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Excellent. Let's go to this section here. What are the big take-home values clinically that you see when you're reviewing with practitioners?

Cat Simmons: Yes, so this page is kind of… You've got your opportunistic bacteria and methanogens, and then you have your fungi, yeast, which are obviously also opportunistic. Page three is a big feature of IMAP. This report isn't the best representation of some of the overgrowth that we find, but these organisms on this page are fairly carefully selected due to clinical relevance. And if you notice on the reference range, some of these are really low, low microbes, not present in very high quantities. So it's a very sensitive technology platform to identify them in stool. Things like Klebsiella, Morganella, Pseudomonas… We get really, really granular information. And on this page, depending on which organisms are overgrown, what the symptoms are, have some favorites. I think I find Pseudomonas to be really fascinating. They're LPS carriers. They actually can partially, they have elastic these enzymes that can gluten and make gluten more antigenic to the immune system. These organisms can, when they accumulate, when they grow up, they do tend to grow up more in the small bowel, and so they can knock down the capacity of your brush border enzymes. They can get in the way of, well, like DAO is on the brush border. Pseudomonas also produces histamine, so you can get, you can get histamine pictures from this, from this page looking at the organisms that produce histamine. You can kind of go on and on. Staphylococcus aureus is a really interesting organism, very pH sensitive, has a lot of correlations with skin. So we have so many patients with, you know, your eczema, your psoriasis. My last consult today was a three-year-old patient who had an E4 level of Staph, really, really, really aggressive with eczema since six months of age. So, you know, connections like that, if there's an obligation, so Klebsiella, and that gets researched, it's a history. It has a lot of autoimmune associations, I mean, by and large. So, um, see, are we breaking up?

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: No, you're good here. But it's interesting you're talking about some of these bacteria producing histamine, right? Because, oh, can you hear me?

Cat Simmons: Yeah, I can.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Okay, yeah, I was just talking about histamine here because you were kind of bringing it up. Histamine, people get very focused on avoiding histamine foods, using DAO, avoiding histamine in the environment. But a lot of times, which that may be helpful, but a lot of times, that histamine sensitivity could be really present in the gut as a root cause through a lot of these things.

Cat Simmons: Overproduction in the gut of histamine producers is definitely a pattern that we look for.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah, absolutely. Alright, so you can keep on going. We're just talking about staff and strep. Go ahead with that

Cat Simmons: Yeah, so I was just kind of rattling of some of my favorites that we have discussion points about… I mean, obviously, with all of these, it's important to kind of just keep the symptomology in mind, you know, the clinical presentation. I don't know, I'm getting a lot of comments that people can't hear me. What do you want me to do?

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah, there's definitely a lag here. We're just going to keep pushing through, though.

Cat Simmons: Alright, I might… Do you mind if I take this headset off because I've been using it all day, it might be dying?

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah, no problem. No problem. I'll let you do that, and I'll keep on riffing here. No problem. I'll let you change the headset here. Take a minute, and I'll do a little review here in my hand, too. Are you able to keep going here?

Cat Simmons: Yeah, I can keep going.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Okay, go ahead.

Cat Simmons: So anyway, we do have these microbes we take all day, we sit here go through each one, line by line, give yoy pearls about them these microbes in our resource guides. You know, you get the hang of this the more tests that you use, the more times you see them. And again, you know, the thing to keep in mind here is these are opportunists. They grow opportunistically, so you have to keep coming back to what is presenting this opportunity. And, you know, it may be low weak commensals, it may be digestive insufficiencies, hypochlorhydria, it may be recent antibiotic use. It might be a combination of all three.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah, absolutely. That makes sense. That makes a lot of sense. Now, what about fungus and yeast? I see this here a lot. I'll run a lot of times organic acid testing side by side these tests, and I'll come up with D-arabinose or D-arabinatol a lot of times when yeast doesn't even come back on here. So I always tell patients when yeast comes back a little bit, it tends to be significant. Can you give me your take on the kind of the yeast overgrowth section?

Cat Simmons: Yeah, so I'm… I mean, remember, we are looking… This test is measuring microbial genomics in stool. It's very specific, and they're specific targets. This yeast collection, Candida being the big one, Candida being the one that gets most of the attention. So a lot of times, people are surprised that we don't see Candida on the IMAP, although I see it plenty. So there's criticisms out there that the GI-MAP does not pick up Candida. Those are… They're invalid criticisms because we see it all the time. I think I had, like, five consults on Candida today. But when I do see it, it's usually pretty significant, in my opinion, and it does relate to Candida colonization specifically in the gut.

And you can have systemic issues outside of the gut for sure. Yes, you can. Yeah, yes, you can. People will pull in things like acid test, you know, Candida antibody testing. I used to work for a lab that did Candida antibody, Candida scrub, so, you know. But I will… I see Candida… You know, it's… You, the digestive insufficiency has kind of a co-infection with H. pylori, quite often. And I see people are really symptomatic when you have Candida overgrowth in your gut. And I see a lot of psychosomatic symptoms, a lot of anxiety, brain fog-type symptoms with that. You know, the organic acid testing you know, I don't know… I don't know what I want to say here, like… Those tests will find it, they'll find yeast probably more often than a stool, like this, but it's not always specific for those microorganisms. So, you know, here, it's like you're finding exactly what you're looking for.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah, absolutely. Yeah, I'll see yeast, you know, I'll see it if I see it at all. Forget it's even flagged. If I see it a little bit, I'm concerned. That's kind of how I look at it. I'll also run D-arabinose, and, you know, I'll see… A lot of times… And I'll run the arabinose as well, just because, like you mentioned, yeast may not be fully in the gut. It could be outside the body, and you may need another kind of systemic net to catch that. So it's good to look at it. I've yet to see a viral issue come back here. Have you ever seen a viral issue in the gut?

Cat Simmons: Rarely, rarely. Yeah, you know, we just don't see the viral colonization they're looking for viral load. You need to do it in blood.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah, I also very rarely see worms too. Let's go to page four. How often do you see worms coming back?

Cat Simmons: Correct. Yeah, I mean, you really shouldn't be finding worms unless you've been to… just not… They're not super common. But we do see the protozoa fairly frequently, at least at low levels.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Exactly. And on the parasites side I see Blasto a little bit, I'll see Dientamoeba fragilis a lot, Endolimax. Which ones do you see the most frequent based on your experience? And then, what kind of symptoms do you typically kind of correlate? The same kind of digestive stuff? Or do you notice sometimes it's not even digestive? Maybe it's mood, it's fatigue, it's brain fog. What do you notice?

Cat Simmons: So I will say that nine out of ten times you see one of these low-level parasites, or even if they're lab-high, again, there's going to be functional patterns that point to hypochlorhydria. They are also opportunists. They won't be there unless you've been exposed to them and your body's been consistent. So that kind of sets the stage. You know, we see Blastocystis, we see Dientamoeba. I do see Endolimax and Entamoeba coli pretty frequently. Sometimes we see them as… And I don't always… You know, with the Endolimax nana and Entamoeba, because I… You don't always need to really take actions. A few foundational pieces, they'll go away on its own. Blastocystis and Dientamoeba fragilis tend to be more tenacious. Blastocystis is a really common co-infection with H. pylori. Yeah yep, yep. And there's a lot of skin, again going back to the skin, there's a lot of skin statistics as well. It depends on the level. You know, there's a difference, I feel like, with these. There's a difference between it being lab high and just detected in terms of symptomology. And a lot of times, when we see these low levels, it's really just, you know, kind of secondary to weak digestion and weak immune function.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Totally. So, if we kind of hammer on some of the skin stuff because I see that a lot, and I always tell patients that the skin is the mirror of the gut. What are the big microbes that you connect to the skin? You mentioned blasto, I think you mentioned staff. What else?

Cat Simmons: Yeah, so, well, H. pylori because of its effect on stomach acid.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: How does stomach acid impact the skin, though? Is it just food not being broken down, fermentation in the gut, and the skin being used as a detoxification mechanism?

Cat Simmons: Yeah, and low stomach acid is an opportunity for other microbes, right? It's this vicious cycle. You've gotta have decent stomach acid, or everything else is for naught. Honestly, it's extremely important. So that's a big one. Blastocystis hominis, Staph aureus, like I mentioned before, and candida. Candida is a big one with skin implications as well. So, those are probably the main ones on my radar. Oh, and then the histamine patterns. So we have, I don't know, six or seven histamine bacteria. If I don't know, Four out of the seven, five of those are detected or elevated, this is histamine overgrowth, and that can obviously have a lot of skin manifestations as well.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: And what are the big histamine ones? You mentioned Pseudomonas, I think you mentioned Klebsiella as well. What are the big ones besides those two?

Cat Simmons: Morganella is a really big one. Pseudomonas is a big one. Staph aureus is interesting. It doesn't actually directly produce histamine, but it activates mast cells, so it's a similar mechanism, I guess you could say, but it's more of a mast cell activator than a histamine producer. Klebsiella is a big one. Proteus is a big one. Citrobacter freundii specifically is a big one as well.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Just curious, do you notice the correlation with the orders of magnitude above the reference range? If you're 1X, 10X, 100X, a thousand X, do you notice an intensification in symptoms, the more the genetic load is?

Cat Simmons: Yes, absolutely. Sometimes you see profound levels, like I've seen pseudomonas at like E9 before. (I've seen it very high like that.) Proteus, you know, Proteus is not one you see every day, but I've seen very high levels of Proteus in patients that present like IBD, but their inflammatory markers look good. I'm like, well, maybe this is just a Proteus overgrowth. But yes, absolutely, and that's the value of quantitative reporting. You can get that degree of magnification. We see Staphylococcus aureus a lot, like we see it all the time. But there's a big difference between a detected E2 level of staff and that eczema patient I saw today that was like high E4. I mean, that's a huge difference, right?

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: And what does it mean when you're going through a protocol, you're supporting digestion, you're supporting enzymes, obviously a healthy diet, you're using a therapeutic level of herbs, and then the levels go up between tests? What does that mean to you?

Cat Simmons: Well that depends. One thing that I think needs to be understood is when to retest. We typically recommend retesting four to six weeks after a protocol has finished, and I think a lot of times that's too early. I had a consult yesterday with someone who, you know the provider, the provider was not the primary, hewas trying to help, he was more of an auxiliary provider, and the patient has been recommended for C. diff, and she was on Vancomycin when she did the test, and the test looked horrible. But there's an effect of being on an antibiotic. We're looking at what is spilling out here. So really, what you need to do is treat, wait, give that microbiome time to stabilize, rebalance, make sure what you were trying to kill back if it's going to, and then retest. I'd say more often things get worse because a lot of times there's retesting too early. So that does happen. But it's also possible that working with the gut is like peeling back layers of the onion. Sometimes you treat one thing and you uncover something else. That happens a lot with H. pylori. You see swapping, I don't know if that's helpful but…

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Yeah and when you say swapping, is that kind of as you're going deeper into the gut lining, you may have borrowed microbes that are kind of working their way out?

Cat Simmons: Right. Or sometimes they're masked on the first test and then they're uncovered on the second.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Interesting. I'm just curious too. We talked about the length of time after the test from being off antimicrobials. Is that about four weeks, about a month or so? And does that also include probiotics? I mean, I think you'd want to be on probiotics to prevent a rebound overgrowth. Would it be about a month or so after stopping herbs?

Cat Simmons: Yes, four to six weeks after treatment, right. As far as supportive supplements, you can be on probiotics when you test, just keep that in mind. If you're on a lactobifido probiotic, your lactobifido are gonna look better on the GI map, (Or even a little too high maybe?) Yeah, just keep that in mind in your interpretation.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: That makes sense. Very good. Alright, so we hit some of the parasite stuff here. Why don't we go down to some of the intestinal health markers? So, just kind of my take here out of the gate. The biggest thing that I like to focus on is elastase and steatocrit because if you don't have good enzyme or acid or… When I see low elastase, a lot of times there's an acid connection because acid's a big trigger for elastase. And also, acid is a big trigger for bile production and lipase from the pancreas. So these, I think, are really important. Why don't you give me your take?

Cat Simmons: Yeah, No, I think you nailed that honestly. I couldn't have said it better myself. Stay adequate is a reflection of fat in the stool. Elastase is a reflection of pancreatic output. We don't have a direct assessment for hypochlorhydria on this test, but often if there is low acid, you will have reduced pancreatic output, and that's going to affect your fat, protein, and carbohydrate digestion. So, yeah, I mean, I think you're spot on there. You know, with this,

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Does taking enzymes, does taking enzymes, would that influence elastase, or would that not? Would it just be exogenous enzymes therefore, it wouldn't bump up your internal production?

Cat Simmons: Correct. We don't supplement with pancreatic elastase-one, so taking enzymes should not, if you're taking supplemental enzymes, they really should not pick up on the lab. You are looking at the ability of how robust the pancreatic function is. So, eating enzymes theoretically should not influence the results. We do see though…

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Got it. But over time, just by getting that gut health better and getting your acid levels up, that would probably, over time, influence pancreatic function to improve.

Cat Simmons: Exactly. Exactly, yeah. And you know, just to add on to steatocrit, there is some element of dietary fat intake in steatocrit. The research shows that Western diets, which are typically higher in fat, have higher levels of steatocrit. So if steatocrit seems anomalously high, do a diet intake. How much fat is this person actually eating? Are they keto? Are they taking oodles and oodles of Omega-3 supplements? Things like that. If something's not quite right, and the other thing, whenever there's a steatocrit elevated, I like to look at serum vitamin D. It's a good place to start because there could be malabsorption of fat-solubles as well.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: That makes sense. Plus, you know, is there a lot of blonde or clay-colored stools? Is the stool floating? Is there excessive streaks or skin marks on the toilet? Those will probably be all good indications as well.

Cat Simmons: Absolutely.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Good, now let's talk about gluten antibodies. If you come back with high levels of gliadin, how I look that as it is, that's indicative of gluten sensitivity, but it may not necessarily be Celiac. Can you expand more on the gluten marker and then Celiac versus allergy, or sensitivity?

Cat Simmons: Yeah yeah yeah. Absolutely. This is my jam! So, this is a secretory IgA antibody response to gliadin protein. Gliadin is the more immunogenic protein found in gluten. This is a fecal secretory IgA antibody response, we cannot use this as an assessment for Celiac, period, end of sentence. To test for Celiac, you're looking at a blood test, looking at tissue transglutaminase-two antibodies, atleast usually with a total serum IgA. I think its imperative, I thuink everyone should be tested for Celiac every five years, if you want my opinion. Unfortunately this test is valuable, but we can't use it as an assessment to Celiac. So what this is a mucosal, immune response to gluten, you know its the mucosal antibodies. it tends to an aggravated mucosal response and increase, the gut does not like this protein, so it is fire the bodies against it.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: That makes sense. So, what are the conventional lab markers that you're gonna use to look at Celiac sensitivity outside of you know, your type of scope that's gonna give you a mrash core which is going to look at the microvilli atrophy? What markers would be more clinical for the Celiac markers?

Cat Simmons: Yeah, that's a good question. I think we're moving towards the gold standard being more of the tissue transglutaminase antibody and deaminated peptide antibodies. If you get a Celiac panel through Quest or LabCorp, that's typically what they're teaching. A lot of practitioners use the “four out of five rule”. In that you well, that test clinical response to a gluten-free diet, genetics. So you can certainly run genetics. They do genetics for Celiac. They do not diagnose Celiac, but you know, they literally state that you need to have the genetics to have Celiac. So there's a lot of ways you can go around it, even this gluten antibody test, our test is exposure-based. If somebody has been strictly gluten-free, really no antibody test will be completely valid. Even biopsy as well, you have to have that exposure to the disease state. So its gets tricky for people, that being said, being 100% gluten-free is challenging, very challenging. I've counseled umpteen amounts of patients it. Even in the most educated person, there's still unfair levels of cross-contamination and hidden sources. You know, I don't know if any of you follow like gluten-free Watchdog. But you know, there are groups of people out there that test foods with their Nema devices, and you know you find it in spices. Yuo find it in things like Philadelphia Cream Cheese. Things that should not have gluten in them unfortunately do and so, this is a pain point for a lot of people. But its nice to have these tests sometimes it can tell you when you're being exposed eventhough when you don't think you are. I saw that a couple times today, actually.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Very interesting and last but not the least, we have these inflammation markers. Calprotectin has been a gold standard for a while, and you guys added this EPX marker last fall. Could you talk about the two and how they differ?

Cat Simmons: Yeah, so Calprotectin has been around for a long time and it is well-established. It is not a diagnostic marker on its own but is part of the diagnostic workup, traditionally in IBD. It has a lot of implications in IBD and it can really use to differentiate IBS from IBD in clinical workup. So that's been around for a long time. Calprotectin, this is a lot of people don't know, is specifically reflective of neutrophil infiltration to the colon, so it is looking at colonic inflammation specifically. There's ton of inflammatory dysbiosis, why is calprotectin in a normal range? It's more like well you got a lot of infalmamtion but it higher up in the bowel.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Got it. So Calprotectin is more in the colon, and then you can have other inflammation in the small intestine that may not represent itself on the Calprotectin.

Cat Simmons: Correct. It's an important protein. We didn't make it up or anything. I will say it needs to have another inflammatory marker because as described, it's very specific to the colon. So Eosinophil Activation Protein can be helpful, but it's very non-specific though, so there's a lot of reasons why it may be elevated. It's a lot of times more of a consequence than a cause, but it can elevate in IBS, it can elevate in food sensitivities and allergies, it can certainly elevate in IBD.

This is one where I like to use numbers. To me, there's a big difference between an EAP at 2.5 and an EAP at nine. At those lower levels of inflammation, it tends to reflect more like food antigen inflammation sensitivities allergies. Barrier permeability on its own can rev up the EAP. At really high levels, then you're getting more into that chronic disease. A lot of times you'll see high EAP with high calprotectin in an IBD scenario.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Excellent, very good. And you said the EPX protein is a bit… it can differentiate between IBD and IBS?

The EPX protein could kind of differentiate.

Okay, got it. Very good. Anything else you want to highlight about the IGA or any other markers here that you want to kind of emphasize?

Cat Simmons: I don't know. We've covered a lot. I mean, zonulin is always exciting. Zonulin's an add-on on the GI map, so you don't always get that on the reports, but I do find it useful. It relates a lot to insufficiency dysbiosis. You're going to see zonulin elevated more so when the commensals are weak, particularly those butyrate producers. I always like to educate on the connection between gluten, gliadin, and zonulin. There is a really strong connection there. We know that gliadin can bind to zonulin and drive its release. So the gluten driving leaky gut thing, there is some reality to that. Zonulin is a good thing to have people resonate with it well. When it's elevated, it can be a strong motivator for compliance when we see it elevated.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Very good, awesome. All right, very good, Cat. Well, I think you dropped some good knowledge bombs here. This is great. We'll put it out here for all the listeners. We'll put some links down below to access the test or access some additional information or references on the topic. Anything else you want to leave us with here, Cat?

Cat Simmons: No. Sorry if we had connectivity issues. You know, we can lack for a part two or something. Thanks for the guest, thanks for hosting me.

Dr. Justin Marchegiani: Absolutely. We'll try to clean it up as much as we can in post-production. Awesome. Well, thanks for being here, nice chatting with you.

Headsup Health free signup: http://www.justinhealth.com/headsup